What Happens to a Dreamer Deferred?

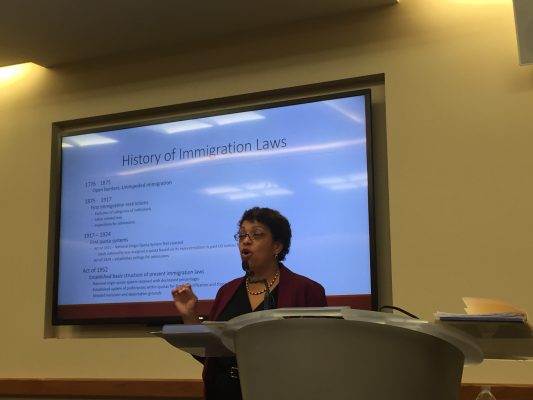

Professor Gemma Solimene spoke in front of students and faculty on Sept. 21 about the legal details of D.A.C.A. (COLIN SHEELEY/The Observer)

October 8, 2017

Professor Gemma Solimene, director of the Immigrants Rights Clinic at Fordham’s School of Law, stood behind a miked podium in the multipurpose room of the 140 Building on Thursday, Sept. 21 as students and faculty shuffled in from an opening in the northern partition carrying plastic plates of pizza. Settling in, Professor Elizabeth Stone, who stood next to Solimene, introduced the former head of the Legal Aid Society’s Immigration Law Unit to an eager round of applause.

Solimene’s subject that day was D.A.C.A., or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, and what had happened to it and the “Dreamers” it protected, but, she prefaced first, such an action can only be understood in the historical arc of American immigration laws.

“The first hundred years of the country, we had these open borders” Solimene said, keeping a black, leather watch on the stand in front of her. “Unimpeded immigration. Between the 1880s and 1917, there is an influx of a large number of immigrants…As those numbers grew, so did the call for restrictions.” That was and is the general correlation.

Following a stretch of restrictions beginning soon after the Civil War that included the “idiots, lunatics, convicts and persons likely to become a public charge,” according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the establishment of national origin quotas, and the everlasting, preferential system of the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952, the throttled borders of the United States breathed one gasp of relief in 1965 when amendments to the previous law threw out national origin quotas, only for the jaws of regulation to snap shut again in the ‘80s and ‘90s with revisions that “rocked practitioners’ worlds,” establishing three to 10-year bans on unlawful immigrants, erecting a second fence on the U.S.-Mexico border, and broadening the eligibility for deportation.

“I would have a client who one day had a means under the law, legal means in order to get status, and literally one day to the next, things change,” Solimene said, tapping her toe. “The laws have changed. They’re retroactive, and now you’re not eligible for anything.”

Then there was the creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Patriot Act and finally, D.A.C.A. The action, which as of 2012 accounted for almost 800,000 individuals whose status either expired or never existed, was rescinded by the DHS on Sept. 5, 2017. Previously, it allowed those without legal status to live in the U.S. and work without fear of deportation. It was a system of enforcement priority.

“Let’s be honest; we do not have the resources,” Solimene said. “The United States government does not have the resources to deport every single individual who is deportable…It’s just not feasible. It’s not possible.”

Solimene changed the slide to a series of quotes attributed to Janet Napolitano who, now the President of the University of California System, was the United States Secretary of Homeland Security under President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013. The excerpts came from a lecture she gave at the University of Georgia in 2014:

“The policy of DACA is rooted in a subset of young immigrants who, through no fault of their own, found themselves living in the shadow of American life,” it read on the slide.

Now there are no new applications. Those submitted before Sept. 5 will be processed, but any permits that expire past March 6, 2018 are no longer eligible for renewal. “There seems to be some doubt” as to what will happen that day, according to Solimene. Until then, many are skeptical of the plan’s legitimacy, but many more are left unsure. At least in that room that day, there might have been some understanding gained.