State of the Institution: Free Speech at Fordham

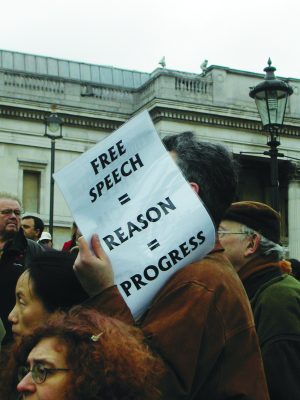

COURTESY OF SIMON GIBBS

Following myriad contentious situations, students and faculty question the university’s responsiveness.

September 2, 2017

“The Board needs to communicate more with the faculty,” Andrew Clark, Ph.D., vice president of the Faculty Senate spoke through a patchy sputter of cell phone reception. “Communicate” was what it sounded like he said. Clark had been an important figure over last year’s faculty health care negotiations; he chaired the Faculty Salary and Benefits Committee, helped organize a silent protest of University Statute violations in February, and later gave a speech in front of a bandaged and crippled crowd of professors who had gathered to stage a “sick-in” rally on the Fordham Lincoln Center Plaza where they voted in an overwhelming statement of “no confidence” in University President Rev. Joseph M. McShane, S.J.

At that moment, he was speaking about the future.

Clark was, of course, only glancing at a portion of the issues Fordham faces in this year ahead. Over the course of his 15 years at the university, he said that he had come to notice a systematic effort on behalf of the university administration to hinder, dissuade and contain the voices and demands of students and faculty in the protection of their own interests. As to what interests Father McShane and the Board of Trustees have, he could only speculate. “Decisions seem to be driven by financial concerns,” Clark said, but there’s no way of knowing until members of the Board express “true transparency.”

Bob Howe, Assistant Vice President of Communications conceded on this point. “We are going to keep people more abreast. You will notice this coming year that the university will be communicating more frequently.” How this new communication would look, Howe could only say so much, but noted that soon, for instance, faculty and staff will start receiving emails and written information about the new health insurance plan.

This was as far as Howe was able to agree, however. In every other respect, it was a matter of diametric opposition. In circles, the vice presidents exchanged remarks–Clark claiming the university has shut the door on the grievances of professors and students, Howe parrying: “Certainly, the administration listens.” Clark arguing that censorship in the inaccessibility of the Fordham alumni network, Howe arguing that contacting alumni is a large part of his job.

The contradictions extended through others’ experiences as well. Sofia Dadap, Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC) ’18, recalled more explicit occasions of free speech transgression. She remembered an October 2016 incident where a Women’s Empowerment counter-protest was visually intercepted by Public Safety vans during a Rose Hill film showing by Respect for Life. Howe had no recollection of the incident, but noted that “it is not unusual for the police to put themselves between protesters, for obvious reasons.”

“We need to make sure that folks are aware about how to go about voicing their frustrations”

The striking division between perspectives amongst the populations at Fordham University points to a larger epidemic of miscommunication between parties. Much like speaking through a spotty phone line, messages and intentions are broken up and misinterpreted.

Keith Eldredge, dean of students at Fordham Lincoln Center, acknowledged this growing issue. “We need to make sure that folks are aware about how to go about voicing their frustrations,” said Eldredge. “I think all parties in a conversation need to be open to compromise.” Otherwise, we lose the signal and we dig in our heels.

Dadap believed this impasse all came to a head after a series of student actions in protest of Dean Eldredge’s veto on the formation of a Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) chapter and the university’s opposition towards the unionization of adjunct faculty resulted in an altercation at the Cuniffe House last April where both sides claimed injury by the other.

An independent investigation concluded on June 15 that the Public Safety officers present at the incident refrained from using excessive force during the incident and acted in accordance with university rules. Before that, in a May 19 email, Father McShane declared a reversal on his opposition to the unionization.

The email noted that his decision was an ethical one. “Though it may not always be as obvious as I’d like, I am sensitive to the concerns of the University community, and I deeply appreciate your input. I would not have made this decision were it not the right thing to do, but in this case, popular opinion and the ethical choice were in harmony,” McShane wrote.

Both Clark and Dadap found that the letter did not give credit where it was due. Clark felt that McShane “gave no recognition to the students” who had nothing to gain outright from protesting. Dadap thought the letter was “fascinating because they’re trying to ignore all the bad press students were giving to the administration…It always happens that people just pretend they come to these decisions on their own,” Dadap said.

She believed that lending little to no acknowledgement to the activism of students was evidence of an authoritative leadership. Clark too, suspected that the administration functioned with “top-down authority.”

On the inside, however, Eldredge described a different world. “I don’t think this is a place where decisions come from on high,” he said. Eldredge and Howe argued that issues raised from within go through a much more democratic process than what might appear. “My experience is that every issue that has been raised–even minor issues get discussed,” Howe said. “Nobody I work with has any hesitation about sharing their point of view.”

That being said, if there was a major divide between either of them and their bosses, it would be grounds for leaving. “If I personally disagreed with something…I would resign,” Howe said, adding, “I wouldn’t tell you anyway” if it were ever that serious.

Likewise, Eldredge, who could not think of a decision by the Board of Trustees or McShane with which he ever had a qualm, stated that he could not allow himself to work in a place that did not consider the voices of its employees. “If I felt like I couldn’t share my opinions, or that my opinions didn’t matter, I’d leave,” Eldredge said.

Student protesters, on the other hand, come up against a completely different scenario. Howe was uncertain of the extent to which a student’s activism can affect real change in some of these decisions. “It can,” he said. Fordham cannot do everything for every individual and, “it’s hard to know if the students in general are mobilized over an issue.” This, in addition to financial and logistical restraints, means there is only so much an administration can do in a year. Call it an “administrative bandwidth.”

“I would not say that it’s easy,” Eldredge said. He mentioned that students in the past have impacted administrative decisions such as the guest pass policy, and the educating the community on the reclamation of the word “queer.”

But students in general are difficult to marshal, according to Dadap. “It’s pretty easy not to care. If these issues aren’t passed down, people will forget about it,” she said. Apathy is a part of the culture at Fordham. She said she hears things from students like “You shouldn’t have come to a Catholic school and expected to change it.” Nevertheless, she is hoping for the small victories, like reforming the sexual health program for Orientation and securing trans-friendly housing.

Clark is also planning for the future. He returned to the vote of “no confidence” which registered almost 80 percent of tenure track faculty, 88 percent of whom supported the state. “That is a resounding ‘no confidence,’” Clark said. “The board has chosen to ignore that, but that feeling doesn’t go away.”