Fashion Industry Photos Provoke Questions of Political Correctness

Vogue India Controversy Illustrates Difficulties of Globalism

June 22, 2011

Published: October 02, 2008

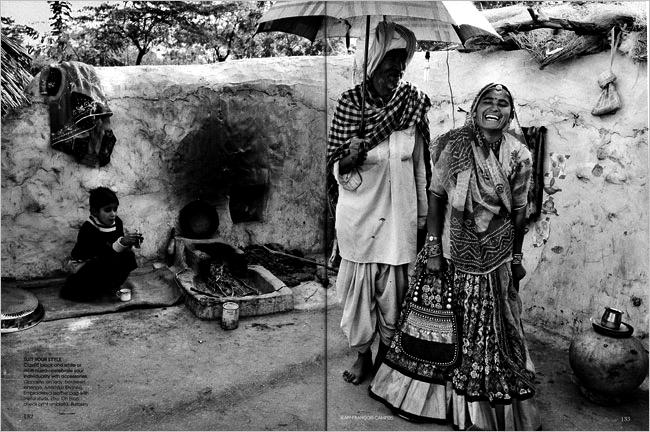

This past August, Vogue India featured a 16-page photography spread to promote fashion items from designers like Burberry, Fendi and Hermes Birkin. These images featured models who were, or at least appeared to be, of the lower class of Indian society. The photographer is Jean-Francois Campos—a well-established fashion photographer who began his career as a photojournalist.

In one example, an elderly woman cradles an infant, who is adorned with a Fendi bib (priced around $100); in another, a family is photographed outside their home, the father holding a Burberry umbrella (priced around $200).

The contrast between the fashion items being marketed and the context they are presented in has prompted controversy, particularly in the international media. As reported in both the New York Times and the Independent, a popular newspaper in the United Kingdom, some people regard these images with disgust. Kanika Gahlaut, who is a columnist for the Indian newspaper Mail Today, told the New York Times that she found the images “distasteful” and “vulgar.” Gahlaut also expressed her belief that the photos come off as insensitive to the plight of India’s destitute.

Yet several individuals have suggested that the images are not as contentious as Gahlaut indicates. Gahlaut’s comments seem sensational when the truth of the economic situation is explored further.

Joe Lawton, program director of the Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC) visual arts department and associate professor of photography, was quick to question the alleged poverty of the “models” in the photographs. “Having spent some time [traveling] in India, I would say these are likely lower middle-class people,” said Lawton. He supported this hypothesis by pointing out that the individuals in photos were clothed and seemed generally well-groomed. Also, what Gahlaut referred to as a “mud hut” in one image, Lawton judged to be a decent home, with an outdoor space and a place to “bake bread.”

These assessments are supported by an article by Nisha Susan in Tehelka, a weekly Indian magazine. In response to the Independent’s description of the images depicting “roadside beggars,” Susan writes that, “Most Indians would recognize that the baby in his lace-up shoes and his family warmly kitted out in layers of clothes are not the abject victims that the foreign dailies imagine.” Susan goes on to quote Clare Arni, a photographer from Bangalore, who says, “I looked at the images and thought they were lower-middleclass people, definitely well-fed and certainly not living on the streets.”

This idea of Western societies misinterpreting the photos was reinforced by Brian Rose, a professor of communications and media studies at FCLC, who questioned, “Does the West have the right to comment on the traditional Indian caste system?” Rose was hesitant to comment at all on the photographs, since he claimed limited knowledge of Indian politics and cultural traditions. He did say, however, that the fashion industry as a whole often tries to be “on the cutting edge” and shocking, as these photos might strive to be.

Yet in this effort, the photographer, Campos, may have failed. Lawton commented that he did not find the photos offensive, nor particularly innovative or edgy. A similar sentiment was expressed by Raghu Rai, one of India’s own most noted photographers, who told Tehelka that he found the photos to be “only average photography.”

Manish Mathur, FCLC ’11 and secretary of the FCLC South Asian students group Desi C.H.A.I., also said he did not find the images offensive. “[The photos] make a statement about the contrast between the rich and the poor in India,” he said. “Having been to India several times, I’ve seen that juxtaposition firsthand and these photos only depict that.Also, I don’t think the editor’s intent was to mock her subjects.”

Mathur is referring to the response of Vogue India’s managing editor, Priya Tanna. When approached by the New York Times, she defended the publication of the images with statements like, “…with fashion, you can’t take it that seriously.” She has also stated that the intention of the shoot was to emphasize that, “Fashion is no longer a rich man’s privilege. Anyone can carry it off and make it look beautiful.”

It seems fair to say that in this, at least, the images are successful. The subjects appear happy and at ease. There is little to no artificial posturing in their relaxed poses. Even some of the designer accessories don’t seem entirely out of place. Lawton examined one of the photos and, before reading the caption, wondered whether a purse was part of the advertising campaign or not. Rai makes a similar observation in Tehelka, saying, “The people look happy, and if you didn’t read the caption, how would you know anything about that bag?”

Perhaps the most significant statement these photographs make is that, even with contemporary ideas of political correctness, interpretation is determined by personal context. Some people, like Gahlaut, will only be disgusted; others, like Lawton and Rai, will see photographs that fail in the endeavor to shock. This controversy is “a real litmus test for globalism,” Rose said.