A Brazilian Novelist on the Run

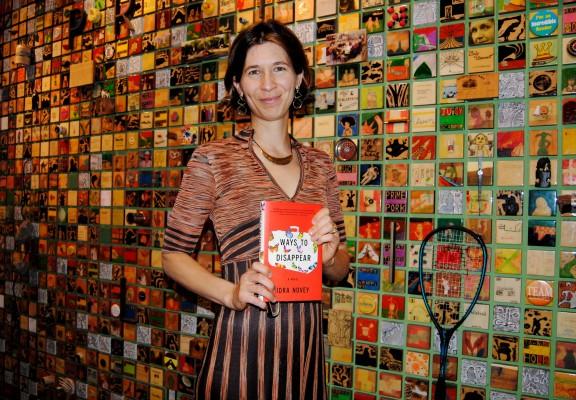

Idra Novey at her book launch of “Ways to Disappear”. (PHOTO COURTESY OF PRINCETON PUBLIC LIBRARY VIA FLICKR)

March 2, 2016

A round woman bearing a cigar and a suitcase climbs up an almond tree and promptly disappears. This is the premise for Idra Novey’s debut novel, “Ways to Disappear,” about a translator who teams up with her missing author’s children to find the writer and bring her home. The novel, brimming with colorful characters, unusual form and an intriguing plot, has charmed critics with its ability to be both lyrical and fun. This critic is among them.

Emma Neufeld, the translator of the missing Brazilian author Beatriz Yagoda, leaves behind a loyal but stifling boyfriend in Pennsylvania to fly to Rio and find Beatriz. Emma’s search for her author is also a search for herself and her writerly voice, as she begins to shake off the translator’s position of being “available yet silent,” where there is “no obvious spot for her to put herself.” The novel is organized into brief, chapter-like sections that read almost like prose poems, or a linked series of flash fiction—the longest section is five pages, and the shortest one is only a few sentences. Interspersed throughout the novel are dictionary entries, radio announcements, emails (many from Miles, the aforementioned loyal-but-stifling boyfriend who insists Emma come home), poems and a police interrogation transcript. These experiments with form help to keep the book playful and unpredictable, which also helps to keep the book in readers’ hands. The reader is not the captive audience of one character’s thoughts, but is instead free to jump around from one character to the next—Beatriz’s translator, Beatriz’s controlling daughter, the wealthy editor of Beatriz’s first works—all the while basking in the hot sun of Rio de Janeiro.

Novey, who taught creative writing at Fordham in the spring of 2015, is a published poet, and poetry does make its way into this novel, both in literal verse and also in rhythmic, image-heavy language. But even greater than Novey’s ability to be poetic is her ability to make fun of the poetic. In one scene, Beatriz compares an unfaithful husband’s distance from his home as “a distance that is not unlike the distance a pigeon keeps from the meaning of its dreams.” Before we can get lost pondering the obscure, ethereal illusion of this metaphor, Novey immediately compares these meanings to “droppings a pigeon may release into the air…sometimes on the bald, unsuspecting heads of men.” Nothing in this book is too precious for Novey’s relentless wit.

Even with the book’s quick, fun nature, simple but profound one-liners regularly stopped me in my tracks. On humanity: “Wasn’t the despair of feeling useless central to the modern human condition?” On translation: “[W]asn’t the splendor of translation this very thing—to discover sentences this beautiful and then have the chance to make someone else hear their beauty who had yet to hear it?” On writing: “[T]o disappear for just a moment into the relief of make-believe—into the plea hidden in every fiction for immortality.” These varying observations seem to come not from a character but from Novey herself, reminding us that Novey is, like Emma, more than a vessel transporting the translated words of a writer, or of a character; she is a writer placing her voice among the voices of her characters, and also the voices of her fellow writers.

As a writer, I found “Ways to Disappear” to be incredibly freeing—this book has no rules. Feel like writing a poem? Write the climax of the novel in verse! Feel like writing a paragraph-long chapter? Write several of them! Feel like introducing a new character in the last 40 pages of the book? Introduce away! This lack of rules is also what makes “Ways to Disappear” such an engaging read; every sentence hums with the knowledge that its writer wrote exactly what she wanted to write, exactly the way she wanted to write it.

Throughout the novel, we are treated with excerpts of Beatriz’s fiction. These excerpts are often autobiography masked as fiction; one story recounts a traumatizing encounter Beatriz experienced in a dark alleyway. Because of this, we might be tempted to wonder: Is “Ways to Disappear,” in part, autobiographical? While it is probably fair to assume that Clarice Lispector—a novelist Novey translated—did not climb up a mango tree and leave Novey to hunt her down (especially since she died in 1977), perhaps it is safe to say that Emma’s thoughts as a translator and professor discovering her voice as a fiction writer are also, at times, the thoughts of Novey, a translator and professor discovering her voice as a fiction writer. Of course, as Beatriz’s daughter Raquel reminds us, with such comparisons we must tread carefully, as knowing a writer’s work is not the same as knowing a writer. As Raquel points out, “What about knowing what a writer had never written down—wasn’t that the real knowledge of who she was?”