Fordham Students React to the Drone Papers

December 1, 2015

In what NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden called the “most important national security story of the year,” the investigative news website The Intercept has published an eight-part exposé about the U.S. drone assassination program based on documents provided by a whistleblower within the intelligence community. The “Drone Papers” reveal the inner workings of President Obama’s covert kill/capture program between 2011 and 2013, a key window in the evolution of the drone wars.

Reporter Ryan Devereaux, in “Manhunting in the Hindu Kush,” part five of The Intercept’s investigation, describes Operation Haymaker, a campaign against Taliban and al Qaeda forces in northeastern Afghanistan. According to the documents, the term “jackpot” refers to an operation that kills its intended target, and anyone else killed in the airstrike is dubbed an “enemy killed in action” (EKIA) until proven otherwise. However, Article 50 of Additional Protocol I of the Geneva Conventions states, “In case of doubt whether a person is a civilian, that person shall be considered to be a civilian.”

Thomas H. Lee, Leitner Family Professor of International Law, considers this classification a possible violation of international law.“If a strike is on a military target in a military setting, and the bomber classifies everyone killed who is proximate to the target as ‘enemy combatant’ killed in action, does it violate the Law of War? Arguably yes, under a strict reading of the Additional Protocol, which the United States did not ratify in large part because of concerns about issues just like this,” he said.

“If a strike is on a military target in a military setting, and the bomber classifies everyone killed who is proximate to the target as ‘enemy combatant’ killed in action, does it violate the Law of War? Arguably yes, under a strict reading of the Additional Protocol, which the United States did not ratify in large part because of concerns about issues just like this,” he said.

Ahmad Awad, Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC) ’17, a history major, called the government’s EKIA classification “very, very bizarre. It’s usually ‘you’re innocent until proven guilty.’ It’s not that you’re an enemy… If they don’t have substantial evidence to prove that it is a potential enemy of the United States and they’re just labeling people as enemies, that’s horrible. That’s not right. That should not be done for people who possibly are just innocent civilians in one of these nations that we are authorizing strikes in.”

Jeanelle Augustin, FCLC ’16, an anthropology major, agreed: “It sounds totally contrary to what we say our own justice model is here in America.”

Sapphira Lurie, FCLC ’17, a comparative literature major, said, “The term ‘enemy killed in action’ had to be invented to imply that those murdered in drone strikes could even be considered a possible threat. So here, the terminology points towards the editorial authority used by imperialists to justify their attacks.”

One document, detailing the period between May and September 2012, reveals that there were 19 jackpots and 155 EKIAs, meaning that almost nine out of 10 people killed weren’t the intended targets. Just months before that, President Obama defended what he called “very precise, precision strikes,” stating that “actually drones have not caused a huge number of civilian casualties.”

“In any other context, that would be a failing grade,” Augustin said. Shady Azmy, FCLC ’19, a psychology major, agreed: “Those are terrible statistics.” “That makes me feel that this drone program that we are doing is not that effective. It’s not an accurate program… that’s a very high collateral damage compared to what they’re saying about low collateral damage. It’s the complete opposite of what they’re intending to do,” Awad said.

The “low collateral damage” that Awad referred to is another of the Drone Papers’ revelations. In a May 2013 speech about drone policy, President Obama said, “there must be near-certainty that no civilians will be killed or injured” before a strike is authorized. But one document, described by journalist Cora Currier in “The Kill Chain,” part three of the investigation, shows that the “near certainty” principle isn’t actually applied to civilians. Currier reports that there must be “near certainty” that the target is present – not that no civilians will be killed or injured – and a “low CDE [collateral damage estimate],” meaning a low chance of civilian death or injury.

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism has been documenting this “collateral damage” for years, finding that between 159 and 261 civilians have been killed by drone strikes in Yemen and between seven and 52 in Somalia since 2002.

Augustin said, “If we’re not sure that civilians may or may not die, it seems to me as though we would be committing terror to those civilian populations.” Alvarez offered a metaphor: “It sounds like a guess and check. That sounds like when I’m writing code, and when I screw up the code, I just have to do it again.” And Awad asked, “What do they consider a low collateral damage estimate? How many innocent lives are lost?”

That same document, which reveals the administration’s two-step process for creating and acting on its kill list, shows that once President Obama approved a target to be killed, Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) had at the time (and may still have) a 60-day window for lethal action in Yemen and Somalia in 2011 and 2012. The administration has nonetheless defended the drone program as a means to prevent “imminent threats” to the United States.

Awad said, “I don’t know how imminent the threat can be if they’re given a 60 day window. I think that an imminent threat would be one that we have substantial evidence to prove that he or she is within a short period of time, has the capability of either attacking the U.S. mainland or attacking a U.S. embassy, or that American civilians are at stake.” Daniel Alvarez, FCLC ’19, a philosophy major agreed: “I feel like that’s way too much time.”

While a 60-day authorization window may seem to Awad and Alvarez an unreasonably long period of time, Lee said it may not violate international law: “The proportionality/tailoring aspects of international law of war are very nebulous, but two months, as opposed to two years, seems okay unless it straddles a peace event that can reasonably be viewed as a material change in the circumstances.”

In the documents obtained by The Intercept, there’s a bevy of corporate language used to describe aspects of the assassination program: the “tyranny of distance,” a reference to the great lengths drones must fly from their bases to targeted countries; “baseball card,” a reference to a slide of information about a candidate for assassination that is presented to members of the chain of command; a slide titled “Manhunting Basics”; “Arab features” to describe someone being targeted; “Find, Fix, Finish,” JSOC’s assassination doctrine; and of course jackpot and EKIA.

Augustin called this language “definitely a mechanism to dehumanize people.” Awad said he was “shocked” by these terms. “It kind of makes it seem that this is a game, and it’s a hunting game,” he said.

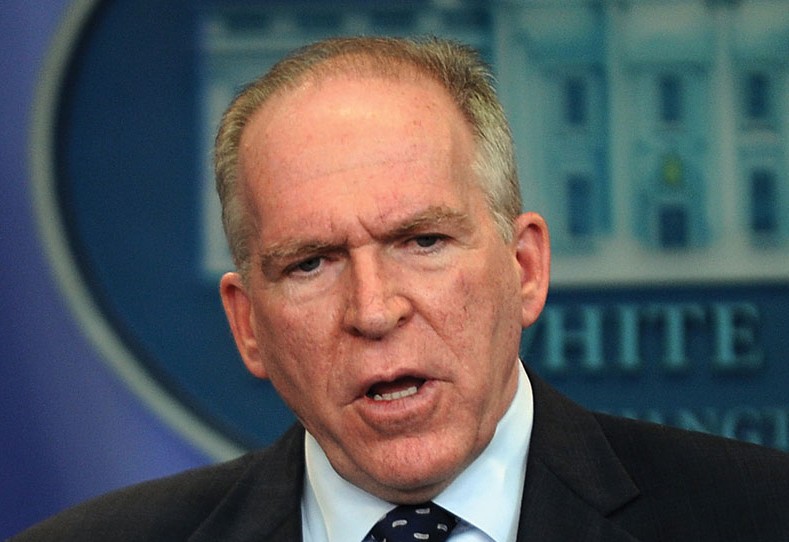

The documents are also a further confirmation of CIA Director and former counterterrorism adviser John Brennan’s, FCRH ’77, role in the drone program, specifically his top role in deciding whom should be killed, portrayed in an illustration by The Intercept. Fordham University awarded Brennan an honorary degree in 2012 and rejected a petition to revoke that degree in this past May.

motoapk thank you • Apr 24, 2017 at 9:13 am

Very informative blog article.Really looking forward to read more. Much obliged.