When “Black Culture” Can Be a Problematic Term

TNS

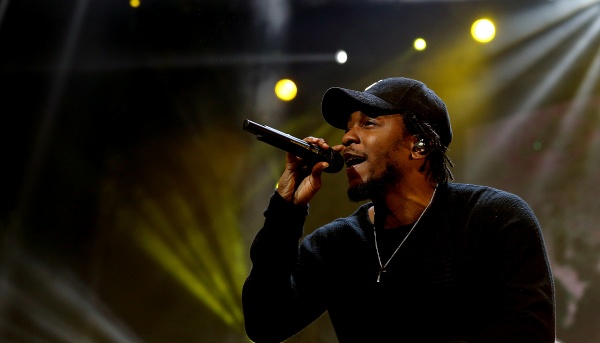

Kendrick Lamar performs during the BET Experience at Staples Center on June 27, 2015 in Los Angeles. (Luis Sinco/Los Angeles Times/TNS)

November 7, 2015

There were two incidents that led me to write this piece. The first occurred when I was reading a Pitchfork.com article about how “white people blatantly appropriate black culture.” The aspect of culture in question was Fetty Wap’s hit song “Trap Queen,” which the author described as “a love song steeped in culling a hard option from dire circumstances.” The culprit of this appropriation was a relatively unknown young white male by the name of Greg Dalton, who, according to the writer, introduces kids “to desperate capitalism and escapist self-medication without any of the aspirational despair and melodic danger” of the original song.

The second incident occurred while I was discussing Kendrick Lamar’s 2015 album “To Pimp A Butterfly” with a good friend of mine. In the middle of the conversation, this individual argued that the album was “a letter to the black community.”

After reading and hearing each respective remark, I paused and pondered. I thought about what unsettled me about the terms “black culture” and “black community.” Then I thought about their similarities. Namely, that they impose homogeneity onto something that is quite heterogeneous. This, I discovered, was my issue with both of these terms.

The “hard option from dire circumstances” that the Pitchfork writer attributes to “Trap Queen” is not an issue shared by everyone who identifies as black. As a middle-class, African-American male, I never felt that I needed to sell drugs in order to put food on the table or help my mother pay rent. Am I therefore excluded from “black culture” because of my experience? Am I, too, appropriating a culture that is not my own when I rap about “cooking pies,” or selling drugs, with my significant other as Fetty does?

In regards to Lamar’s album being “a letter to the black community,” what specific segment of this community is Lamar addressing? Surely the experiences that Lamar raps about are not universal to a group composed of different nationalities, sexes, sexual orientations, religious identifications and, most importantly, socioeconomic backgrounds. How, then, could he be identified as a voice of the “black community,” when such a community cannot possibly be so simplified?

In addition, the terms “black culture” and “black community” raise the question as to what precisely is “black,” and even more, who determines what is black and what is “not black enough.” If we follow the logic of the Pitchfork article, then it is the white, patriarchal, bourgeois, heteronormative media who is the arbiter of “black culture.” Sound racist? That’s because it is. What the Pitchfork article therefore indicates is that these terms are products of the racist and classist systems that have plagued this country since its inception.

Consider, for instance, why we rarely hear the phrase “white community” employed with any legitimacy. That is precisely because we recognize the diversity in this group, and with that, recognize that such a term cannot capture the differences within the group in question. This suggests that we do not accord the same respect to individuals who identify as black. Talk about racial inequality.

This is not to suggest that we should proceed as if the terms “black culture” and “black community” do no exist. Doing so would only suggest an even more troublesome notion: that racism no longer exists. Yet, employing these terms as a means of combatting racism is miscalculated. As noted historian Barbara J. Fields wrote, “Ideologies, including those of race, can be properly analyzed only at a safe distance from their terrain.”

In other words, we cannot combat racism with more racism, as the Pitchfork article attempts to do. Rather, we need to recognize the roots and meanings behind these terms so that we can use them as tools of protest against the system that created them. One way to achieve this is by recognizing “Trap Queen,” and hip-hop culture in general, as a response to not only racism, but its intersection with classism as well. As a result, we can better appreciate the music of Fetty Wap and other artists who spotlight the ills of capitalism, rather than falsely conflating their works as messages to the mythical “black community.”