Central Park Carriage Rides to Halt?

June 19, 2011

Published: March 12, 2009

It’s your one-year anniversary, and you’ve planned a classic, romantic evening for your significant other, who will be astronomically impressed by your meticulous planning and excessive thoughtfulness. You’ll buy them a dozen roses, eat a candlelit dinner at Nougatine and take a horse drawn carriage ride around Central Park. A flawless arrangement, except when you arrive at the edge of Central Park, you discover that horse-drawn carriage rides in New York City have been permanently banned. Since you’re the ideal mate, you’re obviously made equally exhilarating back-up plan, but the rest of the population, which is far less scrupulous, had better begin researching alternate date activities.

Recently, City Hall has been in turmoil over two proposed bills concerning the horse-drawn carriages that line the outskirts of Central Park, just a mere block from Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC). Councilman Tony Avella (D-Bayside) has proposed a bill that would ban the carriage horse industry in New York City altogether, while Councilman David Weprin (D-Hollis) has proposed a bill that would tighten safety regulations for the horses and raise the price of carriage rides.

According to the New York Observer, the two councilmen recently argued their stances at a hearing overflowing with animal rights activists, carriage drivers and ordinary New Yorkers.

Avella first introduced his bill in 2007 after witnessing a horse and carriage accident on TV.

“There’s a reason horse and buggies no longer exist as a reasonable form of transportation in New York City,” Avella said. “Cruelty to animals is no longer appropriate in our society. There have been seven accidents that we know about. Three horses have died, and five people have been injured—and those are only the ones we know about.”

If his bill passes, the city’s carriage horse industry would become obsolete, which he feels would be most beneficial for the safety of both the animals and New Yorkers.

Avella argues that banning horse-drawn carriages will not hinder tourism, something Mayor Bloomberg feared would result from a complete ban.

On the other end of the spectrum, Weprin is advocating keeping the industry in operation but aims to require stricter health regulations for working horses. According to his bill, “Stables in which horses used in a rental horse business are kept shall be [open for inspection] inspected at least four times a year by a single entity that has veterinary training in the care of horses.”

Horses would also have to be inspected twice a year and not be younger than five years or older than 20 years at the time they are purchased.

Weprin’s bill also calls for raising the price of horse drawn carriage rides from $34 to $54 for the first half hour, so you’d better put in some extra hours at the office before next Valentine’s Day.

Though it may seem distant from the lives of many New Yorkers, the contention over horse-drawn carriages has sparked heated debate among the city’s residents, especially on the Upper West Side.

The drivers who rely on the carriage horse industry for their livelihoods have shown overwhelming support for Weprin’s bill and refute claims that their horses are maltreated.

One driver named Andy, who regularly parks his carriage near Columbus Circle, expressed his contempt of these claims.

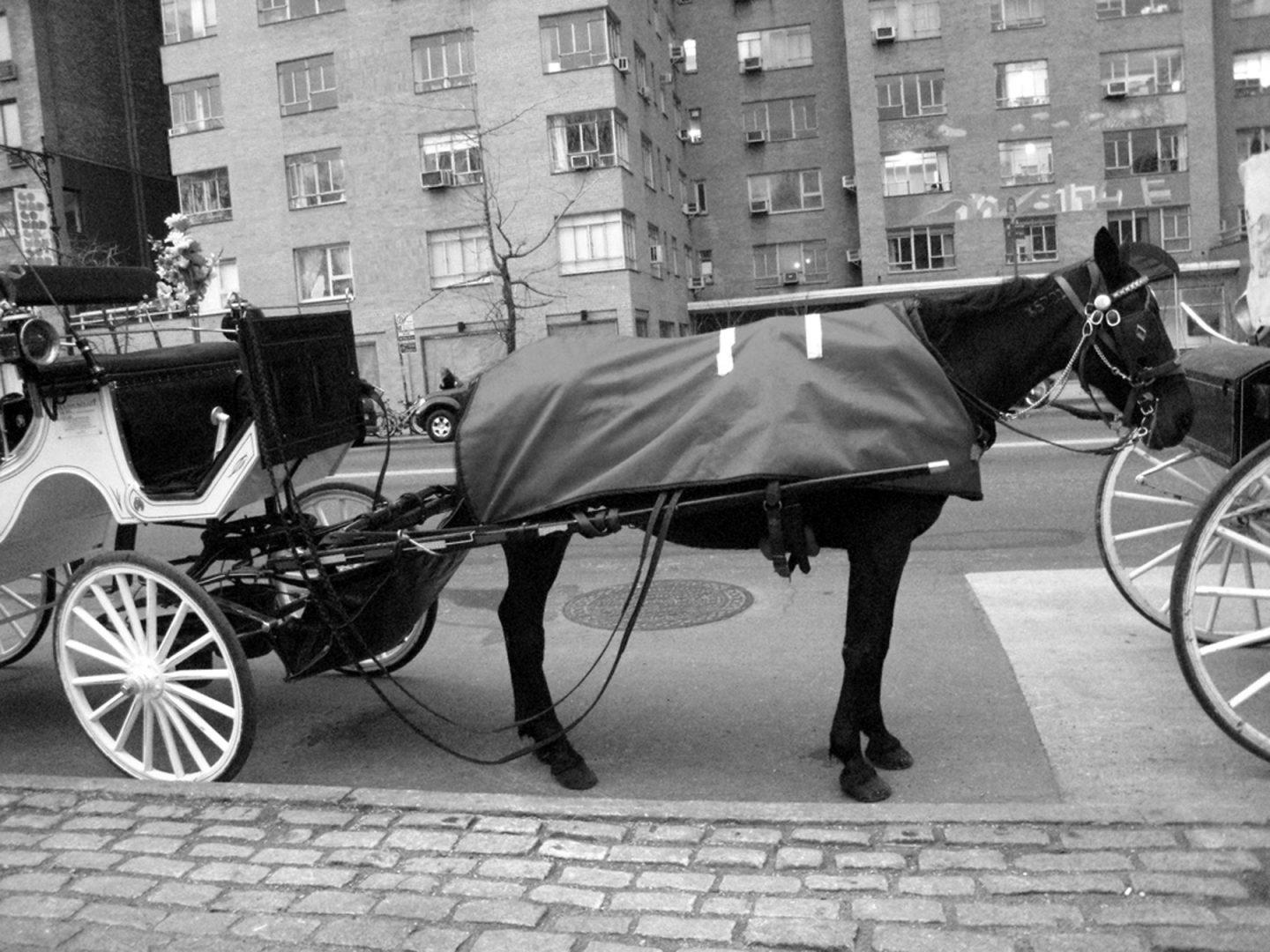

“They think we kill horses. We treat them well. People from Cornell check them all the time. Look at this horse here, do you see any scratches?,” he asked while gently nudging a sturdy black horse named Rocky off the sidewalk.

Besides coping with claims that their horses are being treated harshly, drivers fear for their jobs, which they consider even more valuable due to our nation’s recent economic recession. Andy remains hopeful that his job will be spared when the bills come up for a vote.

“I don’t think they’ll vote against us or this industry,” he said. “A lot of Irish and Italian people would lose their jobs. They’ve been doing this for 35 years. It would be a bad decision in this economy crisis.”

Despite strong support for Weprin’s bill within the industry, Avella claims that, “Other than people in the industry and misguided city officials including Michael Bloomberg and Christine Quinn, [my bill has] had overwhelming support from the public.”

The consensus around FCLC seems to reflect Avella’s statement.

“There is less space [in the city] than if [the horses] were at a barn in the country, so they don’t really get turned out the way my horse in Pennsylvania does,” said Sophia Suppa, FCLC ’11. “[In the city], they’re generally just in their stalls when they’re not working. From what I’ve heard, sometimes they get taken to the country to be turned out. While this is good, it’s probably not enough for what a horse would really want or need.”

Though they mention their concerns about the safety of drivers who may encounter horse-drawn carriages on busy New York streets, FCLC students seem particularly concerned about the wellbeing of the animals in the carriage horse industry.

“Many of the horses that come to New York to be carriage horses have already been used for labor on Amish farms or on racetracks and often have injuries and arthritis, which makes pulling a carriage excruciating,” said Kendra Mara, FCLC ’07, director of community involvement at New York City Animal Haven. “The ASPCA has 21 officers overseeing the business of carriage horses, and they have trouble enforcing the minimal laws that are already in practice. The chance that they will be able to enforce more laws is slim to none.”

Despite hours of deliberation, an agreement has not yet been reached, nor has a date been set for the bills to be voted on. The vastly opposing ideologies make the compromise extremely difficult. One side sees New York City as a technologically advanced place where horse-drawn carriages simply don’t belong, while the other hopes to preserve the industry and the jobs that come with it. Put simply, the two sides have completely different opinions on whether horses should be working.

“You can’t put them in your house,” said Andy, the driver. “They were born for this purpose.”

“The truth is that the practice of horse-drawn carriages has absolutely no place in modern day New York,” Mara said.

Though a resolution may not be on the horizon, one thing is for sure: New Yorkers don’t horse around when it comes to their views on

animal rights.