Don’t Judge A Book by Its Content

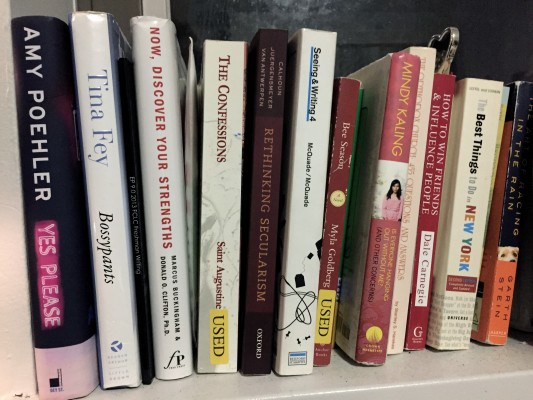

(Maria Kovoros/The Observer)

February 11, 2015

When someone asks, “What’s your favorite book?” chances are many would respond with a classic novel, so-called “real literature,” instead of young adult fiction or “Fifty Shades of Grey.” With the “Fifty Shades” movie coming out Valentine’s Day weekend, they’ll probably keep mum about going to theaters to watch something that has been called “trashy” hundreds of times. Everyone deals with this in some capacity: We are expected to hide behind the guise of what society arbitrarily calls “smart literature” while we are forced to keep secret what we actually like to read. We’ve always been told to never judge a book by its cover, but society forgot to tell us to not judge a book by its content either.

Sure, the writing might be juvenile, but to say that books like “Fifty Shades,” “Hunger Games,” “Twilight” or even graphic novels are not literature (at least not like non-fiction or literary fiction are) constitutes a problem. Trying to redefine literature by excluding certain books and glorifying others shows how ignorant and out of tune with reality we really are.

Literature is a concept that can be both subjective and influenced by time period, culture and demographics. A book is only “trashy” and “immature” when we identify it as such. Literature is not supposed to be so esoteric. Reading some of the mainstream books that have come out today doesn’t make us less intellectual: these texts are in fact more reflective of the time we live in than Homer’s “The Odyssey.”

A 2014 article in Slate magazine, titled “Against YA,” said that adults should be “embarrassed” to read young adult (YA) fiction and should choose intricate and ambiguous plots over those that “wrap up too neatly.” And while many new adult and young adult books feature the cliché “happily ever after” theme, sometimes it’s nice to escape into a plot that turns angst, loss or sadness into some kind of idyllic future. In fact, in 2012, according to Publisher’s Weekly, 55 percent of people who bought YA fiction were over 18 years old. An essay in New York magazine, “The Thirtysomething Teen: An Adult YA Addict Coming Clean,” showed that part of the enjoyment of these texts comes from the escape they offer to their readers: “We can measure ourselves against [the protagonists’] choices and see how we succeeded; we can feel wiser than they are, knowing that what we did then turned out okay; we can also see for ourselves where there might still be room to improve.”

Reading contemporary books about contemporary problems and taboo topics make us more broad-minded and to a certain degree, more empathetic about our own experiences and those of others. Following the trend of vampires, werewolves, dystopia and now romance also makes us even more in tune with society and its evolution. Eva Illouz, a sociology professor at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem published a book called “Hard-Core Romance” and said that “Fifty Shades” “gives us a glimpse at the immense change in values that must have occurred in western culture – as dramatic a change, one might say, as electricity and indoor plumbing.”

Regardless of what we read, we are constantly learning something new. Not to mention, all these popular, mainstream books deal with themes commonly found in the classics. Themes of love and independence are prevalent in all books, whether it’s George Eliot’s “Middlemarch” or some of the mass market romances on the stands of drug stores featuring burly Fabio-esque men and victorian, regal women on their covers. Even though the “Hunger Games” and “Divergent” series are young adult books, they share the dystopian theme with “Brave New World” by Aldous Huxley. Their genres shouldn’t discredit them. Commercial fiction isn’t simply read by people with nothing better to do; there are dozens of scholars who read them, if not for entertainment, for anthropological purposes and to evaluate how societal values are changing.

I probably won’t go as far as to say that Katniss Everdeen is our modern-day Jane Eyre or that Christian Grey is our Mr. Darcy, but the fact of the matter is that they all have similar storylines and similar characters, so to praise one book as literature and not the other is unjustified. Yesterday’s fluff is often considered the classic literature of today. Many books that were too controversial and perhaps too anachronistic for the times they were written in are now books people praise. And while I am not a clairvoyant and will not say that “Fifty of Shades of Grey” will be tomorrow’s classic, I can say that books don’t define us, we define them.