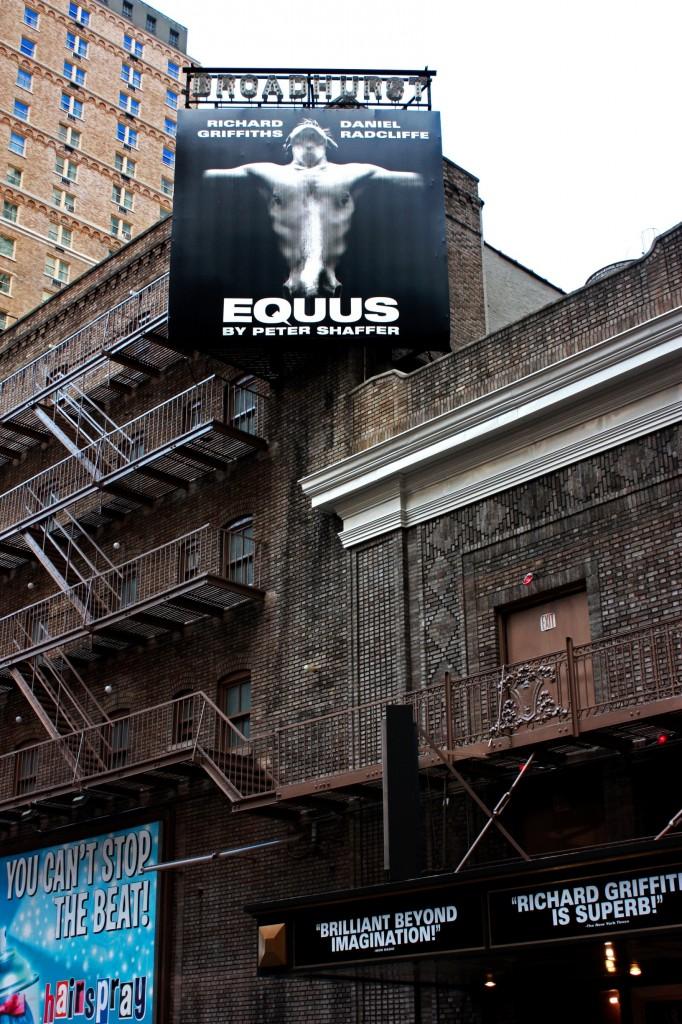

Radcliffe in Equus Revival

June 5, 2011

Published: October 30, 2008

When Daniel Radcliffe first enters onto the stage and begins singing bizarre ad jingles to a confused, wary Richard Griffiths, it becomes very clear that we are not at Hogwarts anymore. This talented pair is starring in the first Broadway revival of Peter Shaffer’s psychological drama “Equus,” which is currently playing at the Broadhurst Theatre. Radcliffe and Griffiths give mesmerizing central performances, surrounded by a supporting cast that is, for the most part, disappointing. Unfortunately, the tone-setting stagecraft also misses the mark.

In “Equus,” mysterious stable boy Alan Strang (Daniel Radcliffe, of “Harry Potter” superstardom), in a mad rage, blinds six horses in one night, and no one seems to have any idea what motivated his horrendous crime. After a social worker brings Strang to a mental hospital, child psychologist Martin Dysart (Richard Griffiths, known to the world as Harry Potter’s despicable Uncle Vernon) is given the task of figuring out—from Strang and those around him—“why-done-it”?

The action of the play occurs in Dysart’s memories of Strang recounting horrible dreams and recollections—which put both patient and psychologist in a hazy world where they succeed in feeling more “complete” to the audience than anyone else on stage, despite their sometimes intense delusions. Radcliffe and Griffith’s performances are appropriately, and effectively, other-worldly and initially remote, because both men, at least at the beginning, put metaphorical brick walls in front of them. Dysart is not even sure he wants to “cure” Strang because, in the boy’s wild-eyed and tortured equine worship, Dysart sees all the passion his own life lacks. Strang, for his part, stonewalls his therapist and is very unwilling to reveal anything about his anguish, initially preferring to sing silly jingles instead of confront his demons. Radcliffe displays an incredible intensity and focus in the role, and his stare is often positively squirm-inducing.

Most of the supporting cast, intentionally or unintentionally, seems to be playing rather two-dimensional characters. This only becomes truly frustrating in the case of Strang’s overwrought mother. Carolyn McCormick sobs hysterically whenever she is on stage, which is maddening. There is, however, one cast member who escapes this 2-D fate: Kate Mulgrew. Playing the social worker who delivers Strang to Dysart, Mulgrew seems to be going for straight realism in what is generally a surrealistic, dreamlike show and, as a result, is a welcome break in the almost unearthly atmosphere of the play every time she enters. Mulgrew’s character represents the much-needed voice of reason—“The boy’s in pain,” she tells Dysart over and over—and Mulgrew’s to-the-point characterization is effective.

In creating the world of “Equus,” the stage effects and set could have contributed to the show as a whole, but instead seem tacky. The stagecraft feels like it is trying to be cinematic which, on stage, inevitably feels hokey. Two minutes into the show, the horses (male actors with metal horse heads and six-inch metal hooves) come clanking out with the clattering sound of metal hoof on grate, destroying the ghostly atmosphere with their distracting noisiness. The horses stalk the stage with unconvincingly creepy LCD-light eyes, altogether too obvious to be powerful or dangerous. Copious amounts of smoke constantly, and often unnecessarily, envelop the stage, as if the director is trying to convey how eerie the atmosphere is when the script and lead actors are doing that to better effect. The visuals are very frustrating—it’s like looking at a wonderful and nuanced painting that has been put in a garish frame.

When it comes down to it, though, the center of this drama is the relationship between Strang and Dysart, and watching Radcliffe and Griffiths work their magic makes “Equus” a captivating theatrical experience.