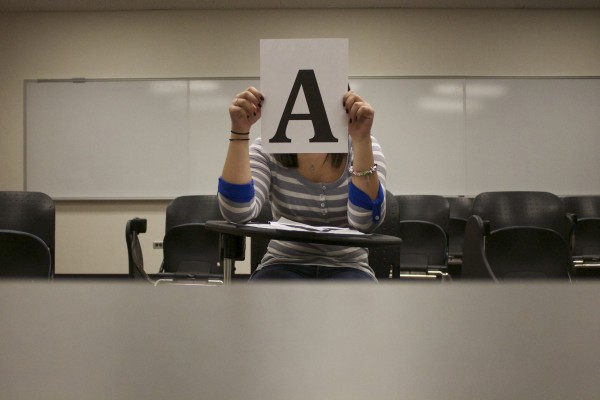

Grade Deflation Hurts Undeserving Students

November 14, 2013

I think I speak for almost everyone when I say that getting good grades in college is important. We often hear from friends at other colleges that they’ve received all sorts of honors for their exemplary academic performance and, as happy as we are for them, it goes without saying that we want the same accolades showered upon us here at Fordham. It’s not to suggest that getting on the Dean’s List is particularly easy at other colleges; it’s just particularly difficult at Fordham because it seems like Fordham makes it near impossible to earn an A.

In the Undergraduate Faculty Handbook, Fordham clearly stipulates that “[w]hile circumstances may vary, a consistent pattern of giving predominantly very high grades will be viewed with concern. Grade inflation hurts students by undermining the University’s reputation with graduate and professional schools.”

While I understand why Fordham would be concerned about lenient professors, Fordham should not discourage its instructors from giving out high grades to those who deserve them. Sure, the “grade deflation policy” motivates us to work harder in our classes, but in the grand scheme of things, it offers somewhat of an unknown future because we can no longer predict how well we are doing in class if there is no direct correlation between our performances in that class and the grades we receive. This grading policy not only lowers our GPAs, but it also hurts future plans that involve internships, jobs and graduate and professional schools.

I remember taking a class last year that I—fortunately—did well in, but getting that high grade was much more difficult and convoluted than it should have been. The instructor was a very strict grader and did not give out A’s unless the work was near perfect. While I understand that earning a coveted A is no easy feat, giving handfuls of students an A or even a B should not be considered grade inflation if the students’ work truly reflects those grades. Professors should not be expected to downgrade a student’s work for the sake of keeping the class average at a C.

A troubling aspect of Fordham’s “grade deflation policy” is that the future of our financial aid becomes uncertain. Most federal programs, such as the Tuition Assistance Program and Pell Grants, require students to have strong academic standings in order to continue to receive more funding. If recipients start to get lower GPAs due to a grade deflation policy at their school, it may affect their aid packages. Average or slightly below-average grades show these programs that scholarship winners are not doing well in school when, in actuality, the problem is that their grades are not appropriately reflecting the work that they do.

Internships and jobs are no different. They may not put as much emphasis on GPAs as graduate and professional schools, but they may still reject applicants who have the appropriate qualifications but do not have high GPAs. Many jobs and internships come with a certain GPA requirement—aside from relevant work experience, they don’t really have any other way to determine how promising we are as students and how knowledgeable we are in related coursework.

Of course, it’s expected for Fordham’s curriculum to be rigorous given its prestigious academic reputation; however, there is a fine line between having strong academics and deliberately depriving students of good grades for the sake of maintaining this rigorous front. Our GPAs are a reflection of how we did in our undergraduate school. If they are subpar, then they suggest that we may not be able to handle graduate coursework or related work in our future careers—even though for many of us, that could not be further from the truth. Grade inflation may hurt Fordham’s reputation, but grade deflation hurts our reputation with employers and admissions boards at graduate, law and medical schools.

https://www.dhgate.comproduct/2018-russia-kokorin-player-version-soccer/408756720.html • Apr 11, 2018 at 8:31 am

It sounds like someone started this project, to tell the truth, and someone else said not to much.

[url=https://www.dhgate.comproduct/2018-russia-kokorin-player-version-soccer/408756720.html]2018 Russia Soccer Jersey[/url]

Janis • Jul 11, 2017 at 9:19 pm

I have to disagree with Amy. Fordham does have grade deflation. Not only that, Fordham has fixed grading which means that professors are instructed to give fixed portion of As, Bs and Cs. As are given less than Bs ecetera. This is what my professor directly told us after our mid-term exam. Also, I know couple of kids who transferred in from state university who had told me that it is much harder to get above average grade than their previous schools.

Amy • Feb 24, 2014 at 5:35 pm

As a fellow Fordham Student, I would have to disagree with this article. The professors at Fordham give students fair and deserving grades depending on how much effort the students put in and if they deserve it or not. No wonder, this is in the opinion section because Fordham does not have a grade deflation. Grades are earned, not given like this article makes it seem.