“Chasing Chaos” in Humanitarian Aid

October 22, 2013

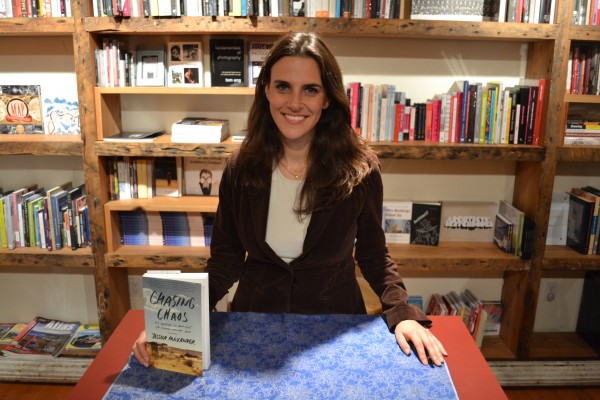

On Oct. 15, Jessica Alexander, Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC) professor of international humanitarian affairs, released her book “Chasing Chaos: My Decade In and Out of Humanitarian Aid,” which she is now beginning to promote on a tour. The book is a memoir and chronicles her life in war-torn Darfur and shattered Haiti as an aid worker; her work, private life and world view changed as a result of her travels. The Observer spoke to Alexander about her work—the distant locales, the 100-hour weeks, the fleeting romances, the loneliness, her respect for the peoples she worked with—and how Fordham students can start a career in this field.

The Observer: Give us some background on who you were before your travels—did you always know you wanted to do this work? What appealed to you about it?

Jessica Alexander: In college, I did a lot of internships at the Childcare Center which is a part of the Department of Health and Human Services. I did a lot of domestic work based on child rights…so I always had an interest in social issues and doing work that felt more meaningful. When I graduated college, I [actually] worked in the private sector, and it took personal circumstances or events in my life to realize that’s not what I wanted to do; I wanted to go back into this more meaningful profession. I went into it at a pretty young age, around 24, and it was really difficult to get my first job or first foot in the door. Typically it requires years of experience or masters degrees and I didn’t have either of those. But, I got my foot in the door and I really loved it; it combined my interest of social issues and my personal desire to travel and see the world and learn about other cultures and be involved in some of the most pressing issues of our time, globally.

Observer: How did you “get your foot in the door” as you said?

J.A.: I applied for every job that I saw online, everything from administrative assistant to program officer, and I didn’t even hear back from these places. I was doing marketing in the private sector—that was my first job—and so I tried to think of how I could use that skill as an entry point. I found a small but growing development organization that needed a PR manager and I basically just hounded them over and over again until finally, the hiring manager returned my call. I got an interview and I got [the job], and it was really fortuitous. I stayed there for about two years, then I applied to graduate school and from there, it just exploded.

Observer: What first gave you the inspiration to write this book—can you trace it back to a single moment?

J.A.: I always kept journals and I wrote very long emails home; people were very enthusiastic and wanted to hear more. I realized that there was a real desire for people to understand this kind of work and the places I was going [to]…it really came together when I would come home from these trips and I would talk to my college friends who were doing very different things than I was, and I realized they had very mixed conceptions of humanitarian aid—everything from ‘does everyone you work with have dreadlocks’ to ‘you’re such an amazing person and I feel better about myself just talking to you’—this saint complex. I found that neither of this was really true obviously so part of this was to demystify this world of humanitarian aid and who humanitarian aid workers are in the industry we work in. The second part is that I would come home and there’d be a natural disaster and people would be very eager to help…I just felt like a lot of these very good intentions went wrong in the field and caused more harm than good. Americans are extremely generous and want to give, which I think is a particularly admirable thing about our country…I wanted to give people a better idea of where their money goes and how they can best help.

Observer: The book chronicles your work in Darfur and Haiti—but you also mention “alcohol-fueled parties and fleeting romances, the burnouts and self-doubt.” How did those ultimately shape your world view and affect your work?

J.A.: Aid workers are human beings just like anyone else. These ‘alcohol-fueled parties’ that I write about are after 3 weeks of 100 hours back to back…it’s not all about the partying; it’s not a party scene, it’s a way to blow off steam in some extremely [challenging] settings. Finding ways to feel normal is important to remain sane and ultimately be more effective at your job. Are there romances? Sure! But, it’s like any place where you find young, ambitious, smart people: they’re going to hook up. The environs are right for that; that’s just part of the world that humanitarians work in. We’re usually very young and unattached and working on adrenaline and no sleep in these very challenging contacts. Of course we’re going to find a way to blow off steam; that is just normal and human. And we don’t do it in a disrespectful way that’s like streaking the refugee camp; if there are just opportunities for us to come together and let our hair down and relax, we’re going to take advantage of that.

Observer: What would you say was the most difficult thing you dealt with in your travels?

J.A.: Personally, sometimes just the loneliness. Teaching at Fordham, I see a lot of romanticism about aid work and the life that you lead, a lot of times it’s extremely lonely. You’re out in the bush; people don’t speak your language. You’re the foreigner and so you look different and you act different and people treat you differently. For me, personally, that was the hardest. For me, spending long stretches of time alone…sitting there at night with these things spinning in your head without an outlet to talk to, it’s very challenging. And sometimes you’re seeing really horrible things…I can handle going without showering, the crappy food, but after a while [having no one to talk to] begins to nag on you.

Observer: What is the ultimate message you want to convey?

J.A.: One thing the media overlooks is that the first responders and sometimes the most effective responders are the people themselves. They’re not hopeless victims just waiting for a handout. There is a need for the humanitarian system to underwrite a response when governments are overwhelmed, but people from these countries are portrayed as helpless victims. I’ve met some of the strongest, most resilient victims who’ve handled these things much more bravely than any Americans would (Alexander later added “Of course many Americans show bravery and resilience in the face of difficult circumstances– families who lost loved ones in 9-11, soldiers in or returning from war, families who were displaced after natural disasters like Sandy. But it’s hard for us to imagine the day to day endurance it takes to live in a country beset by chronic conflict or endemic poverty”)…I try and put faces to these numbers, point out individuals; these are the people affected by this, and they’re not that different from you and me…. Another thing that I write a lot about is about when people just show up to a disaster, well-intentioned people, but without a clue as to how to coordinate within the system, sometimes causing more harm than actual good…Be mindful of how best to help, and sometimes that’s just money.

Observer: Do you have any advice for hopeful Fordham aid workers?

J.A.: For Fordham students that want to go into aid, it’s a great opportunity to learn another language. If you want to go into aid, learn a language; I’d recommend French or Arabic…I’d take classes on international affairs and learn how the aid system works, some of the global politics involved and the economic and social issues that face these countries. I’d intern at an organization that is doing something internationally or domestically and try out this work.

“Chasing Chaos” is now available on Amazon.com and Barnes and Noble. Alexander will be speaking at Fordham on Nov. 21. at 6:00 p.m. in the Cafeteria Atrium, where she will engage in a discussion with students and sign copies of her memoir.