Point – Counterpoint: Liberty and English For All

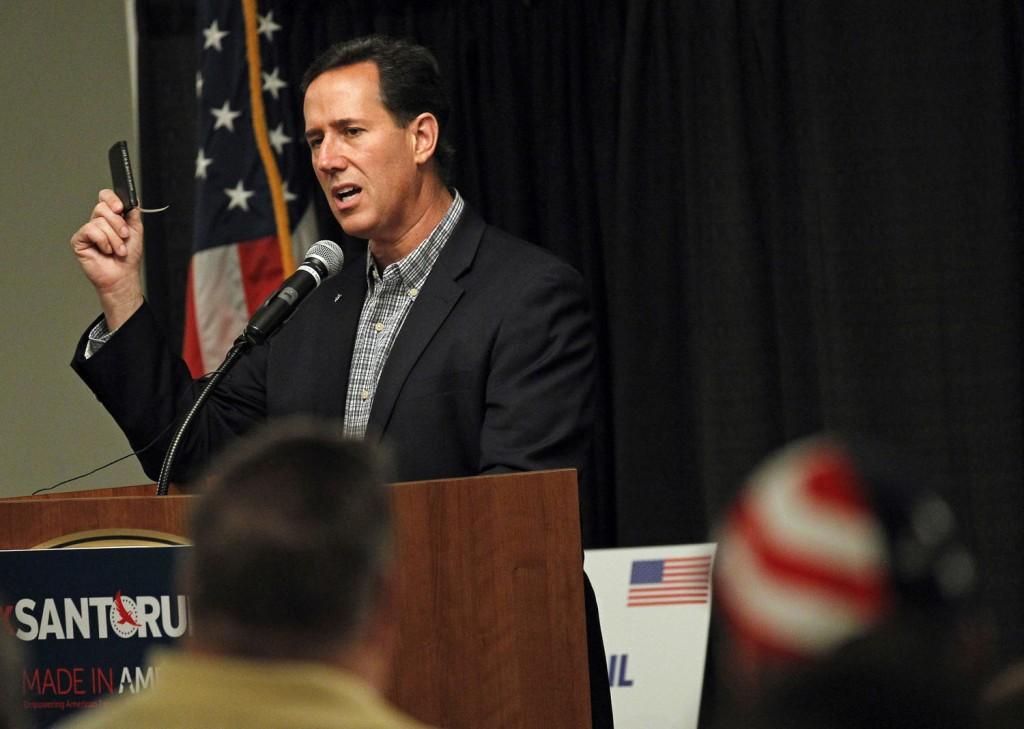

Rick Santorum’s comments on statehood for Puerto Rico stirred the debate on whether or not English should be its standardized language.

May 2, 2012

By NINA GUIDICE

Recently, Rick Santorum said— in Puerto Rico—that for Puerto Rico to become a state, by federal law it would be required to speak English. Yes, he was wrong because that’s not true, but was the sentiment entirely wrong?

There is nothing, absolutely nothing wrong with being bilingual. In fact, I believe that all children should be required to learn a new language in their years of schooling. People who have a non-English native tongue should keep that language close. They should celebrate it. They should speak it as freely as they want to, and no one should begrudge them if they choose to speak that language predominantly. But that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t also have a handle on English.

As a Puerto Rican, most of my relatives are bilingual, with their Spanish being stronger than their English. From firsthand experience, it definitely hinders them. School is more difficult; jobs are harder to come by. At home, I love when my family speaks Spanish, but language is an important part of upward mobility. In turn, upward mobility in the United States is partly predicated on the idea that everyone speaks the same language.

Now, am I advocating there be adequacy tests everywhere, that everyone be required to speak perfect, un-accented, grammatically correct English? No. I mean, George W. Bush didn’t speak perfect English.

And of course there are racial undertones to the English-as-a-national-language argument, especially in this time of controversial immigration policies. Some people are xenophobic. Some people just want all would-be immigrants to stay where they’re from or go back to their homelands.

But like it or not, America is mostly an English speaking nation. Many states require that politicians be able to read, speak and write in English. Most businesses require you to speak English before they hire you, and it becomes more imperative the higher the job level. For example, take the recent incident in Arizona in which candidate Alejandrina Cabrera’s election to the governing board in San Luis was challenged on the basis that she was not proficient enough in the English language to serve. She was serving a bilingual border city, and admitted her difficulties in English while claiming that her level of proficiency was “fine for San Luis.” But the question remains, who is gauging what “fine” means? I propose a national standard, not a regional one.

Encouraging people to speak English in a predominantly English speaking society shouldn’t be a controversial statement. It’s practical; it’s pragmatic. People who speak only Spanish, or only Chinese, or only Arabic will have difficult “making it” in the United States. The same principle would apply in another, non-American setting. Would I hope to become successful in say, Japan if I didn’t speak Japanese? No. I couldn’t hope to be a politician in Russia, or a CEO in Italy if I didn’t speak those languages. Every citizen of the United States should be able to communicate with each other; every citizen should have an equal shot at success. Speaking proficient English is a fundamental step in that direction.

By SARA AZOULAY

Rick Santorum, a former candidate for the presidential republican nominee, said that English would have to be Puerto Rico’s main language if they did eventually become a state. Although Santorum is thankfully no longer a possibility for the Republican candidate, there are two things that bother me when people say that Puerto Rico should have English as their first language. Firstly, both English and Spanish are currently their official languages. That’s right; Santorum was demanding that English be an official language, when it already is. But besides this, there are people who believe that if Puerto Rico became a state, it should speak English solely and Puerto Rican language should be secondary.

As a Puerto Rican myself, I believe that this is a tiny island with a lot of flavor and culture. To say that Puerto Rican culture is not already touched or influenced by American culture would be a lie. Becoming a state would probably change some things in the country. But, the one thing that should remain untouched is their language.

Language, among many other cultural aspects in Puerto Rico, is a defining factor of their culture. Puerto Ricans have a culture that is very strong, tough and loving. Asking them to require that their main language is English would be sabotaging a sacred part of the Puerto Rican culture. Because that’s something that is theirs, and theirs alone. Puerto Rico has never been a truly independent country. Their culture and language has influences from Taíno, Africa, Spain and Europe. Puerto Rican Spanish, like other dialects of Spanish, is unique to it’s own. It should remain a big part of Puerto Rican lifestyle.

Think about the different states in the United States. New York dialect is different from South Carolina dialect. I know that we’re all speaking the same language, but the culture of each state shapes the way we speak to each other. Spanish may be a different language, but Puerto Rico already takes steps to include the English language in their culture. All of my Puerto Rican cousins can speak English well. So, why should we demand that they stop speaking a language that reflects their history and culture?

I’m not saying that it shouldn’t be a requirement to speak English on the island. In fact, most of Puerto Rico does speak English now even as a commonwealth of the United States. The schools teach mostly in English, already. As a state, I think some things will change (like the fact that Puerto Ricans will finally be able to have a voice in their government) but their language should remain the same. If and when Puerto Rico becomes a state and the question is asked: Are you American or are you Puerto Rican? I think Puerto Ricans can easily say both—without compromising their culture or language. English should be a part of their country if they ultimately become a state, but we must recognize and value Puerto Rican Spanish too. American culture will touch their island in another way, if they become a state. So, no creo que inglés debe ser el primer lengua de Puerto Rico. I do not believe that English should be the primary language of Puerto Rico.