The Lost Art of Empathy: New Book Reveals Us to Be Accepting Yet Insensitive Generation

April 18, 2012

It’s been a little over one and a half years since Rutgers freshman Tyler Clementi committed suicide after his roommate, Dharun Ravi, filmed his personal life. The incident shocked the nation. People wondered, what could have been going on in Ravi’s head? Did his Twitter posts and webcam taping have something to do with the fact that Clementi was gay? No. Despite his actions, Ravi professed that he was not homophobic. And gay or not, did he have no conception of how his roommate would feel at this intrusion of his privacy?

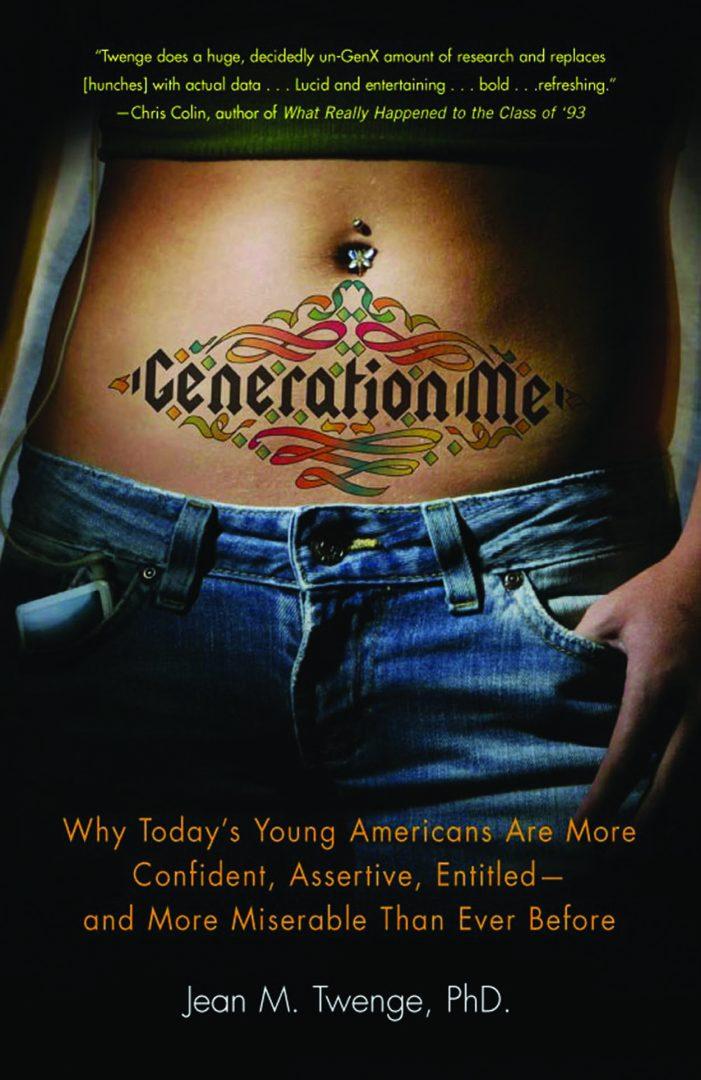

A recent article titled “Generation Me” by Jean M. Twenge published in “The Chronicle of Higher Education” asks what’s behind three disturbing, yet contradictory trends in teenagers according to various psychological studies. Twenge even wrote a book on the subject, and apparently, our age group has increasingly less empathy and is less likely to take responsibility for our own actions, yet we are also more tolerant toward minority groups and more likely to believe in equality more than ever. How is it possible for us to be both tolerant and unempathetic? Is it even possible to have these ideals while crucially lacking what seems to be the essential character component behind them? Ravi, while ‘tolerant’ of Clementi’s orientation, still failed to consider something as basic as his roommate’s feelings as a consequence of his own actions.

A trend of low empathy is increasingly evident in our culture. The popularity of reality TV demonstrates that we find enjoyment in voyeuristically watching intimate details of other people’s trainwreck lives in all their lurid glory. There’s a reason “The Hunger Games” is so popular: its picture of a dystopian world where prime entertainment consists of children battling each other to the death is incredibly timely.

Few people would dare openly attack someone for a reason like being a different orientation or race. Even the recent bias incidents on both campuses were committed in more discreet, surreptitious ways. We live in a time where these labels are socially unacceptable. But the motivations underlying them are not. As a result, we find new and increasingly creative ways to find differences between people now: the way they behave, the way they act, the things they like, the people they hang out with, etc.

We are a generation of contradictions. I’ve seen people committed to making the world a better place, to fighting for social justice, human rights, all the lofty ideals which, as liberal, educated young adults, we take pride in having. Yet in their private lives, these same people make cruel comments and make fun of their peers without blinking an eye. And it’s not as clear-cut that only ‘bad’ people are unkind to others. ‘Normal people,’ like you and me, engage in this type of behavior all the time. In fact, it’s become part of our daily lives.

We hear a racist or homophobic joke, say “that’s awful” but still laugh at it. We don’t hesitate to use derogatory terms like “bitch” not just to people we dislike, but even people we don’t know and often even to our friends as terms of “endearment.” It’s common to say something mean about someone but preface or follow it with “I feel bad.” If we feel bad, then why do we do it?

We’re clearly aware of what we’re doing. Our generation has some strange sort of paradoxical self-awareness that allows us to be aware of our own moral failings but still not do anything to change them. We excuse and justify ourselves, saying some people deserve it, or make ourselves feel better because we’re not as mean by comparison to others. Maybe we’re too self-involved, encouraged by our worlds of Facebook, Twitter and social image, to notice or care. Maybe we’re just exposed to so much information and stress on a daily basis that we’ve become desensitized. Perhaps we feel we just don’t have enough time, or truly believe that the things we do and say don’t have much of an impact.

It’s possible that all these things mean nothing or that I’m just being too sensitive. But I think there’s something deeper and more troubling about the flippancy with which we handle other people. We’ve found a way to distance ourselves from each other’s pain. There’s a difference between real empathy, the genuine ability and effort to understand and feel yourself what someone else is feeling, and simply believing in tolerance and equality in name and at face value.

Bullying, name-calling, and general unkindness aren’t necessarily new things. But their scope, avenues, and degrees of intensity are definitely facilitated with the Internet, Facebook and other forms of technology. While we may not intend to be malicious, it’s not that large a step from smaller, everyday moments of unkindness to what Ravi did. Ravi probably had his own justifications for his behavior toward Clementi, and yes, Clementi’s choice was ultimately his own, but we must realize that there is still a line between what is and isn’t acceptable. Some things do have potential to create serious lasting damage, and that thinking twice about our actions and their possible consequences is worth it in the long run.