“Unconfessed” Author Tells All: Q&A: Yvette Christianse

May 30, 2011

Published: December 13, 2007

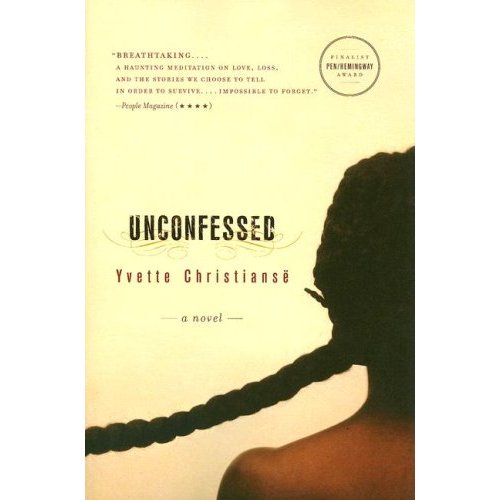

Sila, an African slave woman, is wilting away in a Cape Town prison, circa 1825. What’s her story? Why was she sentenced to death and then pardoned? Intrigued? Then pick up Dr. Yvette Christiansë’s first novel, “Unconfessed.” Christiansë, an English professor at FCRH who specializes in 20th Century African-American literature, postcolonial literatures and theory and critical race theory and poetics, recently saw “Unconfessed” debut in her home country, South Africa. “Unconfessed” was received there with open arms, glowing reviews and a lengthy book tour. The Observer had the chance to sit down with Dr. Christiansë and discuss her accomplishments.

The Observer: Where did you find the inspiration for “Unconfessed”? I understand that you lived in South Africa during the apartheid.

Yvette ChristiansË: I was born in South Africa and grew up with stories about slaves, although no real history class dealt with this subject when I was going to school. You might say that I wrote the novel in what felt like a large silence—felt because, if one takes the time and really listens and researches, that silence is not what it seems. There are always traces, signs, glimpses.

So, while researching a larger, scholarly project about the direct, first-person slave narratives of the Cape Colony, I came across some records of Sila van de Kaap. It is tempting to seize upon these traces of slave voices and treat them as evidence of resistance to slavery. But my fiction was born of another speculation: what if there had been a slave narrative, and what if it was not in a familiar form? How might one imagine the voice of a person who was not writing her own story?

The Observer: Was it difficult to write “Unconfessed,” and how long did it take to write?

YC: The novel went through seven drafts for its American, Dutch and Spanish editions, and then an eighth for its South African homecoming. In total, the writing and drafting took about three years. The research took about 10, which included the three years of writing.

I wanted a form that would do justice to this woman’s story and ended up with a novel that begins in third person which is interrupted by the first person appearance of Sila, who speaks for the rest of the novel. The decision liberated Sila’s voice from that same, imprisoning archive. The other benefit was that, because the novel is so fragmented, the truth of colonialism’s and slavery’s violence is visible—the fragmented nature echoes what is in fact a truth; namely the colonial archive was only interested in keeping only, in Sila’s case, a small, criminalized record of a life.

The Observer: I’ve been told that you just recently got back from South Africa after “Unconfessed” was published there. How was the book tour?

YC: The South African book tour was a homecoming for the novel. I was so nervous about its reception there. History is still a space of real contest and there are certain people who are still apologists for Afrikaner history. There were rumors that some were ready to be offended by the novel and there were rumors of outrage before it had even hit the stands. Fortunately, some of the old possessive economy about who gets to own history and tell it has been dissipated around the novel, which is well received there… so far. I must say this: in the over 24 interviews that I did in six days, every single interviewer introduced me as a professor from Fordham University. It was a lovely sense of pride, to hear that, and also to see it in print. It is important for people outside of the U.S. to know that Fordham exists as a leading university. It’s good for all of us here who work to make this the place what it is.

The Observer: Do you have any advice for the aspiring writers that want to eventually see their work published?

YC: Write. Write. Write. Ink on paper. Writing is a commitment one makes to oneself—to do more than be dragged through life by language, but to try and get some small purchase on it, to understand it, to really engage the world through this only way we have… through language.

And then…be unafraid of revising. That means you might actually have to give up loving your own words too much. One of the most fantastic, liberating moments comes when you realize that you can cut something. Perhaps the degree to which one falls in love with a particular phrase, or a page of one’s own writing, might actually be a mask for a deep fear that, if altered, all other writing will vanish. Not so!

The Observer: Do you have any additional comments you would like to make to The Observer readership?

YC: Slavery in the Cape Colony, and in almost all places where Europeans had instituted slavery, was racially determined. As someone who grew up under apartheid, I am acutely aware of this history and its relationship to the founding of what would become the Republic of South Africa. While the agency of ‘non-whites’ troubled apartheidists, apartheid law could not fail to recognize those who opposed it ideologically and morally. One only has to turn to Mandela’s speech from the dock during the Rivonia trial to see this and to hear the Court’s response—a grudging, shocked recognition of something from which apartheid’s ideologists could not turn. But what made Mandela’s speech possible, and what made its force recognizable? The answers to these questions underline further differences between slavery and apartheid, and it was these differences that I had to address in the novel.

It’s difficult to imagine how constrained the opportunity was for speaking in the time of slavery. In my book, I wanted to address the complete lack of access to advocacy that Cape Colony slaves had.