Superman Leaves the Supermarket: Remembering Norman Mailer

May 30, 2011

Published: December 13, 2007

“Nobody could sleep. When morning came, assault craft would be lowered and a first wave of troops would ride through the surf and charge ashore on the beach at Anopopei. All over the ship, all through the convoy, there was a knowledge that in a few hours some of them were going to be dead.”

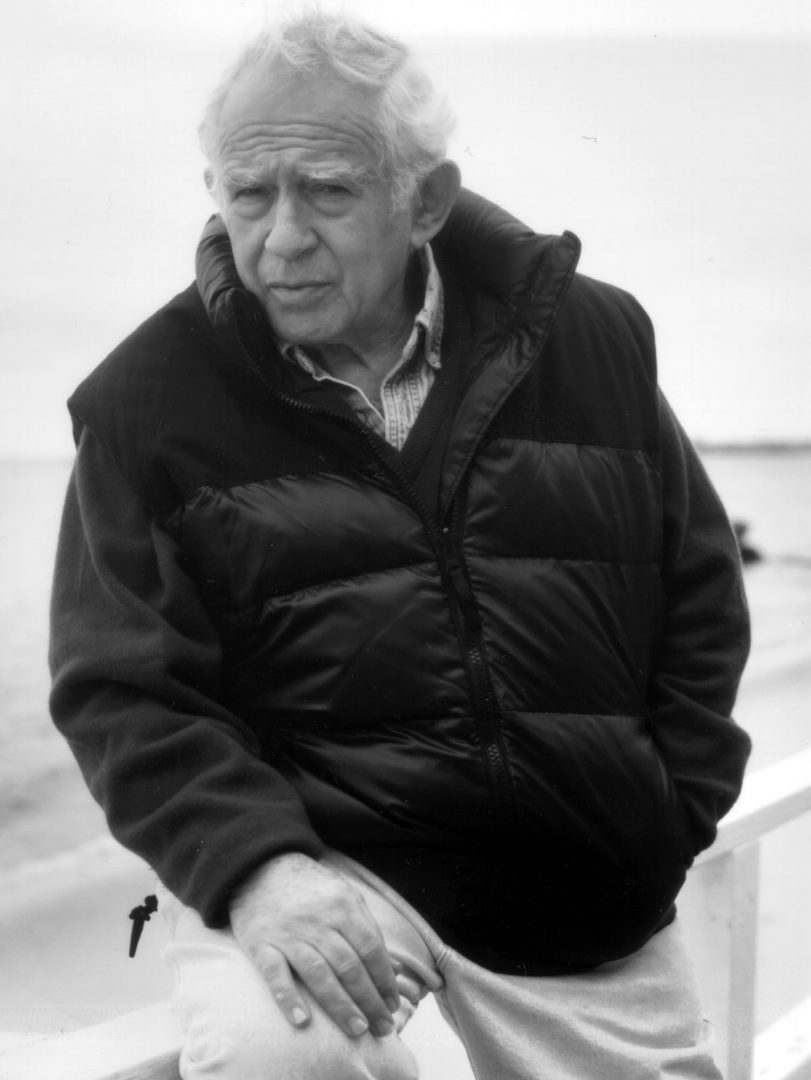

These opening lines of Norman Mailer’s 1948 debut novel, “The Naked and the Dead,” introduced the world to a literary talent both brash and moral, as concerned as he was controversial. Mailer’s words took on a new meaning on the morning of Nov. 10, when he died of acute renal failure, leaving the world with a vast and varied body of work and a personal history that reads like a cautionary tale.

In the few years after Mailer burst onto the scene with “The Naked and the Dead,” he published two more novels, “Barbary Shore,” in 1951, and the sexually graphic “The Deer Park,” in 1955. It was in that same year, though, that Mailer took what may have been his biggest professional step. Along with Dan Wolf and Ed Fancher, Mailer published a small, weekly newspaper initially distributed solely in Greenwich Village. They named their paper “The Village Voice,” and with its creation, Mailer would go down in history as one of the founders of New Journalism, a literary movement that, through works by the likes of Tom Wolfe, Truman Capote and Mailer himself, elevated creative non-fiction into a viable art form and influenced an entire generation.

The Village Voice also served as an outlet for Mailer to hone his craft as a political essayist, the role that he may best be known for. In the following years, he would go on to write several pieces that stand as some of the most lasting pieces of journalism from the 20th Century. In the fall of 1957, Dissent Magazine published “The White Negro,” in which Mailer took a stab at explaining Beat-era race relations by pointing out a certain co-opting of Black culture by white youths who had become dissatisfied with their bourgeois upbringings. This essay would come to serve as an inspiration for further discussion on the “hipster” culture of the ’50s and early ’60s.

Three years later, Esquire would publish what would come to be known by many as Mailer’s early political magnum opus, “Superman Comes to the Supermarket,” a chaotic but poignant look at the candidacy and political machinery of the soon-to-be-elected John F. Kennedy. Unfortunately, 1960 was also the year that saw Mailer stab his second wife, Adele Morales, with a penknife while at a party, an incident that many have pointed to as a sign of personal and literary misogyny. It would also not be the end of Mailer’s domestic troubles. At the time of his death, Mailer had had six wives, and his penchant for affairs and bitter divorces has come to define him almost as much as his journalistic successes.

That being said, Mailer’s legacy is one that is, certainly, built on a foundation of innovative writing and literary ubiquity. He managed to stay relevant for the whole of his life, winning a Pulitzer Prize for his 1979 novel, “The Executioner’s Song,” and publishing a steady stream of well-received works up until his death. Earlier this year, Mailer released his final novel, “The Castle in the Forest,” which examined Hitler as a product of incest. In The New York Times’ review of the book, Lee Siegel wrote, “So let it be said, once and for all: Norman Mailer is a rebellious angel who never fell.” Indeed, despite his flaws, Mailer’s immense influence on those who came after him ensures that, even after his death, he continues—and will continue—to stand tall.