Tabloids or Textbooks? Popular Culture in the Classroom

March 7, 2012

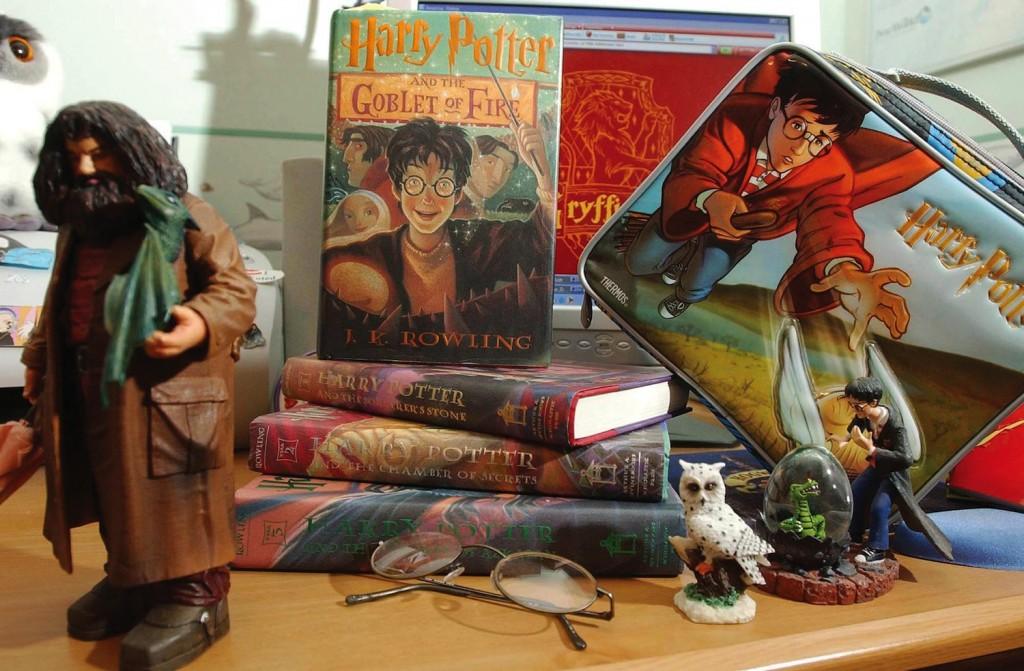

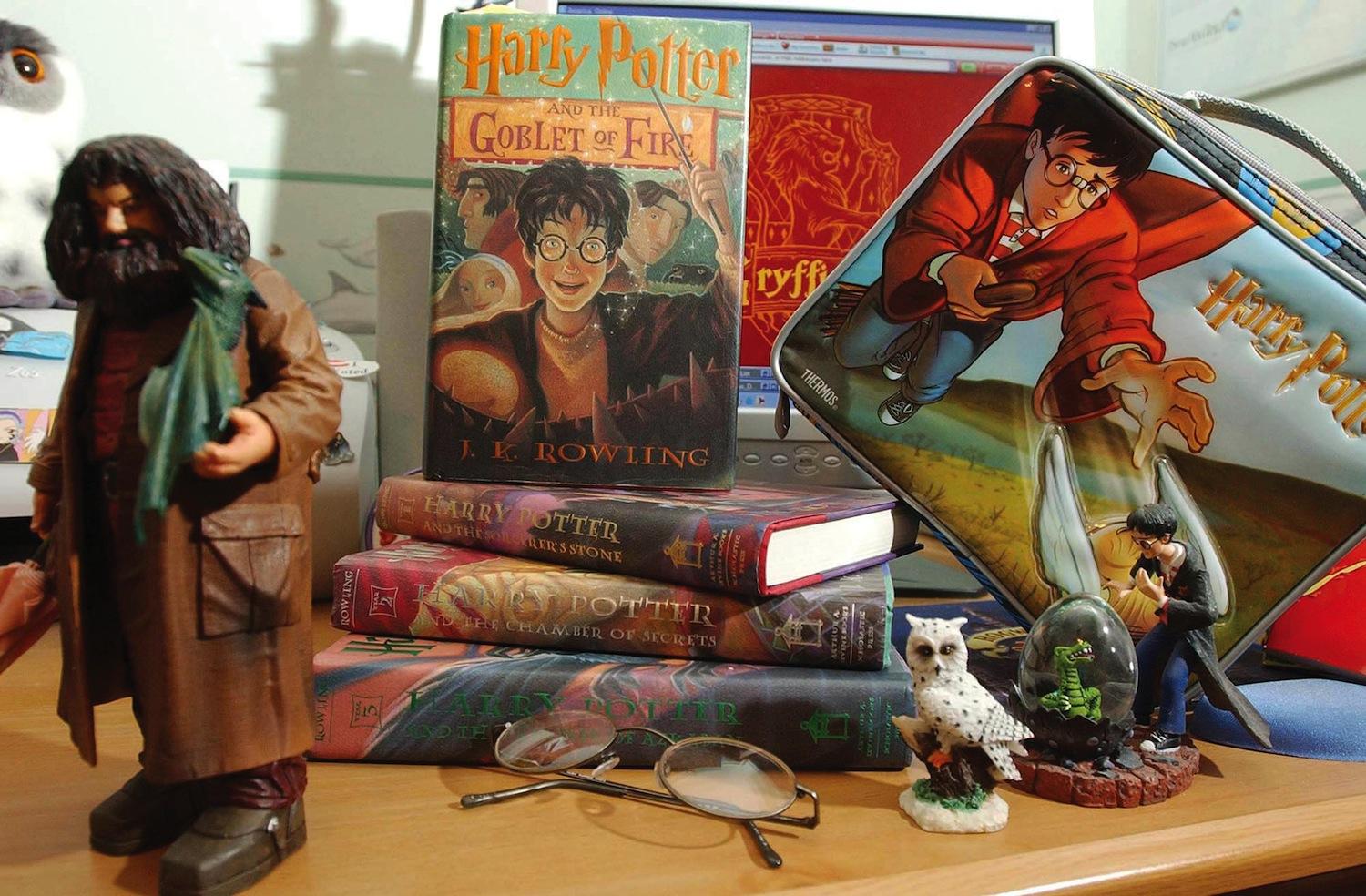

Last year, a course called “Harry Potter and Philosophy” was offered at Rose Hill for spring 2012. This is part of a countrywide trend of colleges integrating popular culture with education. Rutgers University has a class titled “Feminist Perspectives: Politicizing Beyoncé,” which explores issues of gender, race and sexual politics through the lens of Beyoncé’s career, music and videos. University of Virginia similarly uses Lady Gaga to discuss feminism and gender and sexual identity in “GaGa for Gaga: Sex, Gender, and Identity.” Rutgers’s “Vampires: From Sin and Exile to Sex and Salvation,” capitalizes on the Twilight phenomenon to explore world religions and The Old Testament. Columbia’s “Zombies in Popular Media” rides the wave of TV’s The Walking Dead and films like Zombieland, and CUNY Brooklyn’s “South Park and Political Correctness” picks apart war, religion and assisted suicide.

“Harry Potter and Philosophy” is grounded in philosophy, using the books as a base point from which spring discussions about empathy and otherness, ethics, power, love, the nature of mind and self and metaphysics. Students read classic philosophical texts by authors ranging from Nietzsche and Machiavelli to Arendt and Aristotle, and then relate the readings to events, people and ideas in the Harry Potter books.

The emergence of pop-culture-based courses has prompted a discussion of their value. Those who support the trend say that grounding education in topics like Harry Potter can be a powerful and valuable way to teach and learn. Rebecca Etzine, Fordham College Lincoln Center ’12, says it provides an avenue into serious education: “It can be a way to make it more accessible and relatable. There’s a sort of myth that pop culture automatically dumbs things down when in fact it can elevate your thinking when you draw connections.”

Drawing these connections can be an antidote to the frustration that academia is too removed from students’ daily lives and too often descends into abstract intellectualizations. Pop culture provides a common ground for students and, as something they are already inherently interested in and care about, has the potential to make a subject more relevant and engaging to students. This argument is part of Professor Jones’s motivation: “I think people feel a sense of convergence of different aspects of their lives in the course. For me, that’s what education is about—life coming together with the aid of a variety of focal points. Education can’t be mechanical.”

There is also, however, the opposite concern: that pop culture topics are too shallow to merit serious academic consideration. Will students really walk away with as deep an understanding of the meaning of life from studying Keeping Up With The Kardashians as they would from studying Dostoyevsky?

Part of the issue with popular culture, perhaps, is rooted in some sort of elevated regard for the past. Popular culture is part of our present, but many topics of academic discussion hail from a comfortable temporal distance of at least 30 years. English Professor Mary Bly, who teaches a graduate course on Shakespeare & Popular Culture, says that even Shakespeare was not taken seriously in his own time. “It definitely would have been thought absurd to study Shakespeare academically during his lifetime,” Bly said. “He was an enormously popular author, but he wasn’t considered in the top rank of literary authors by any means…he was writing in a denigrated genre—drama was considered too low to merit consideration from serious scholars.”

In many cases, pop culture and academia simply have different goals: academia is oriented toward intellectual enlightenment, while film, TV and music moguls are often driven by nothing more than a desire for money, which can result in the deterioration of pop culture to nothing more than simplistic entertainment. Still, it would be too easy to dismiss all entertainment as pointless to study.

Zach Dorado, FCLC ’12, thinks that the specific academic discipline to which pop culture is applied affects its legitimacy: “Pop culture can be studied in a sociological way, as it affects how people see themselves and the world, and how they interact with it. To study certain works of popular culture as literature is to insult the intelligence of students. It’s like saying that they cannot handle reading and studying literary work which has nuances, depth, or something to say about humanity or the universe.”

Instead, popular media can be used as a barometer for understanding a society. Mark Naison, who teaches a history course called, “Rock and Roll to Hip Hop: Urban Youth Cultures in Postwar America,” said, “You can learn a great deal about a society by studying popular culture, but only if you connect your analysis to a society’s political, economic and social development.” His course, for example, deals less with contemporary hip hop and more with popular music’s historical value in connection with “broader trends in American society in areas ranging from the labor market to gender relations, to race issues and questions of war and peace” and how it became “a powerful narrative of the America urban condition.”

Pop culture has to be applied carefully to the classroom, and when done right, can be enlightening. Dean Mark Mattson, for instance, finds the value in pop culture to be in its potential for interdisciplinary study: “I have learned a tremendous amount from interacting with sociologists, philosophers, archivists, writers, musicologists, musicians, business professors, etc. as we try to understand a complex real-world phenomenon.”

And after all is said and done, maybe the most obvious appeal is that these courses make learning fun. Professor Judith Jones, who teaches the “Harry Potter and Philosophy” course, warns that “Too much education is Voldemortish–disparaging of things it does not care to understand, like children’s stories, house-elves, imagination and love. A course about something the students and the professor equally love…allows learning to be about imagination and joy, which in the end make us human.”