Ramses Debate

April 17, 2023

Return of the Ram(eses)

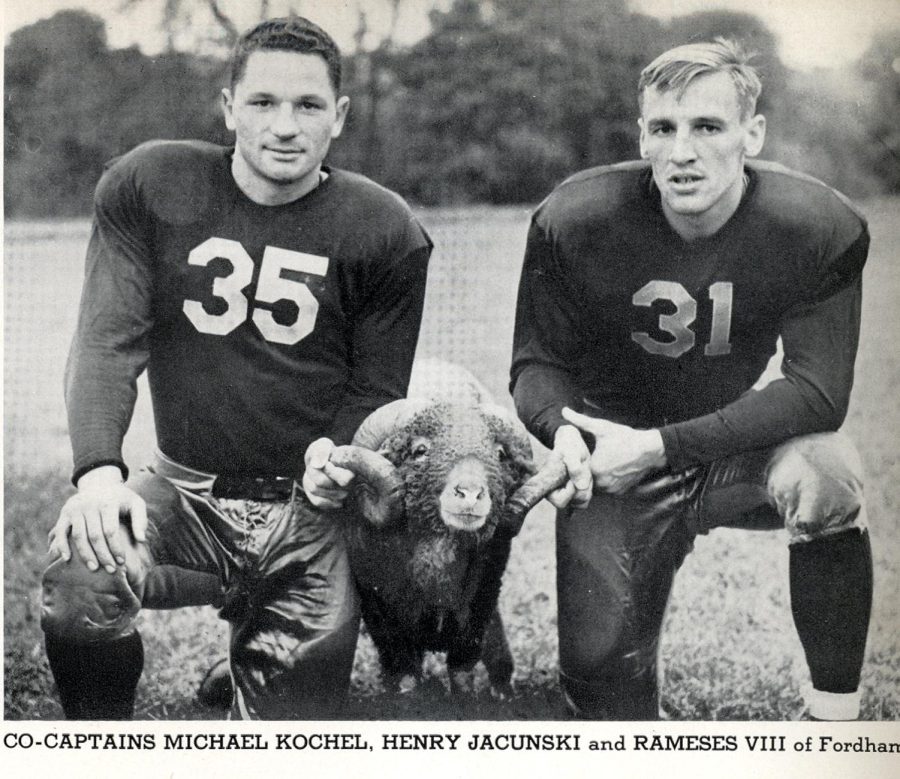

COURTESY OF THE FORDHAM UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Fordham could dedicate a specific area of campus as an ethical habitat for the ram.

Have you ever wondered what happened to Fordham’s beloved live ram version of our mascot? The last ram, Rameses XXVIII, died in 1978 and was replaced by a student dressed in a ram costume. Until last semester, I didn’t know that Fordham had a live ram as a mascot, but I have adopted the firm belief that Fordham should bring the tradition back.

A real ram would be a great face for Fordham, and students and faculty alike could have an opportunity to take care of the ram. Not to mention that Rameses would be extremely popular. I mean, just look at Archie Tetlow’s Instagram. He has a cult following! Imagine the following Rameses could amass!

Michael Lewis, a marketing professor at Emory University in Atlanta, made a surprisingly simple observation on why schools have used live mascots in the past: “Human beings love animals,” and live mascots function as a more motivating and adorable representation of a university than a person in a suit! (No disrespect to the people who bear the honor of bringing Rameses to life. In fact, I salute you.) Seeing a live animal as the face of a university is a more compelling embodiment of the university for students, alumni and fans.

The ram would be a great marketing tool for Fordham to utilize and bring more exposure to the university, offering various opportunities on social media and in the news, especially in those feel-good segments at the end of broadcasts.

The benefits of having a live ram as Fordham’s mascot are not limited to raising morale, though. The ram would be a great marketing tool for Fordham to utilize and bring more exposure to the university, offering various opportunities on social media and in the news, especially in those feel-good segments at the end of broadcasts. With this strategy, Fordham could reach more potential applicants.

The caretaking of Rameses also enables the creation of new job opportunities for professionals related to farm animal caretaking and veterinary services. Caretaking for Rameses would include veterinary services for general health, hoof health and grooming. Caring for Rameses would offer an opportunity for Fordham students to obtain a prestigious caretaking position that would look great on their resumes, which could come in the form of an internship or a work study position.

In addition, Rameses’ presence could lead to the creation of a new animal care program, similar to that of Penn State University’s; a new animal science major exclusive to the Rose Hill campus; and additional courses related to animal caretaking. This academic program and course expansion would enable Fordham to venture into more applied science fields and would appeal to potential students interested in these fields, due to Fordham’s location and proximity to other animal care-related opportunities in the metropolitan area. These opportunities could come from the Bronx Zoo and the Central Park Zoo, the various veterinary clinics throughout the city, and other animal relief and caretaking programs located in New York such as the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), the Animal Care Centers of NYC (ACC) and others.

Given the (often dramatic) losses of the 28 Rameses of the past, it is important that Fordham takes extra precautions to ensure that a live mascot would live a long and happy life.

With a previous dynasty of 28 rams, it is no question that there is precedent for a live mascot at Fordham. The first Rameses made his debut in 1925, and the great dynasty ruled for a whopping 53 years until the death of Rameses XXVIII in 1978, after which the university replaced the live mascot with an animal costume. Given the (often dramatic) losses of the 28 Rameses of the past, it is important that Fordham takes extra precautions to ensure that a live mascot would live a long and happy life.

However, it is important to acknowledge that the practice of having live animal mascots can quickly become unethical. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, more commonly known as PETA, gives the practice of live animal mascots an F. Arguments against the practice cite animal abuse due to the stressful environments of games; concerns regarding their habitats; problematic school traditions relating to harassment and aggravation toward the mascot; and concerns over the animal’s mental, emotional and physical health.

Louisiana State University (LSU) has a Siberian-Bengal tiger mix named Mike. Mike used to travel with the football team until an incident in 1970 in which his cage overturned on the highway. In another incident, Mike was tiger-napped and released before a game, resulting in him being tranquilized. Students used to bang on Mike’s cage before games to hear him roar. There was an old tradition where Mike was put on display in a cage and subjected to cheerleaders using his cage for their routine and electrocution from a cattle prod to make him roar. The United States Department of Agriculture placed a citation against LSU, calling for improvements to his habitat and ending the dangerous practice of parading Mike in front of large crowds. In 2017, LSU stopped the practice of bringing Mike to games after 59 years. However, LSU continues to have a live mascot on their campus.

Due to the ethical concerns over the premature and early deaths of many live mascots, the pair of rams could become a protective factor for their health and could allow them to live longer.

While I am in favor of bringing back a live animal mascot, I want to bring attention to the ethics surrounding having them, and I argue that the use of exotic and nondomesticated animals, such as the University of Texas’ Longhorn steer, the University of Auburn’s golden eagle, the Air Force Academy’s falcon and Baylor University’s black bear, need to be banned outright. However, within the context of domesticated animals — such as dogs, cats, horses, livestock and small rodents — I think that there should be an allowance for them with strict guidelines and regulations.

One key issue with hosting a live ram is that livestock animals are social creatures. Fun fact: Cows have best friends and experience distress when separated from them. Animals that live in flocks or herds must socialize with others from their species. It would make the most sense for Rameses to come back not as just one ram but a pair. Rams do not like living alone and enjoy peacefully coexisting with each other. The Rameses diarchy would be a more suitable living environment as the ram would not be socially isolated, which would be better for the social and physical health of the rams. Facing isolation places a social animal under extreme stress and makes them more susceptible to contracting illnesses. Due to the ethical concerns over the premature and early deaths of many live mascots, the pair of rams could become a protective factor for their health and could allow them to live longer.

The rams would need year-round shelter for braving weather conditions, feeding and storage of the equipment needed for their maintenance. There is a wide range of opinions on the amount of sheep livestock that can live on an acre: One source I found claimed two sheep per acre, and another argued anywhere from six to 10. They would need to have their land rotated for grazing and would need to have fencing around their acre. Fordham could certainly make room for two rams on the Rose Hill campus.

Additionally, this pairing would make for better conditions for when the Rameses-es attend events, as they could reduce stress for one another by having their responsibilities divided. In regard to game attendance, the rams either should not attend games at all or only be brought out at one part of the game, be that before, at halftime or afterward. A whole game attendance would force the rams to be subjected to the loud, crowded space and bright lights, which is not an appropriate situation or environment for them.

With all these considerations in mind, is there an ethical way to host a ram at Fordham? Yes. We can bring back Rameses to continue the live ram dynasty, but with a modern and ethical twist.

Fordham, Don’t War With PETA

COURTESY OF THE FORDHAM UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Fordham had a live ram from 1925 to 1978. It would be unethical to revive this archaic tradition.

If there was a room in which all members of the Fordham community were present — staff, students, administration, the Argo Tea ladies, etc. — I cannot imagine a single person would raise their hand when asked: “So! Who’s going to take care of the live ram?”

Maybe this is a bleak outlook, but I doubt anyone would stand up, impassioned by their secret love of recreational veterinarianism, and donate the level of care and devotion a live animal needs. If a live ram were introduced to Fordham’s campus, to graze in the cigarette butt-ridden lawn of Edward’s Parade, I believe it would ultimately end in disaster.

Fordham doesn’t exactly have a shining history when it comes to our live mascots. We kept actual rams as our mascots from 1925 until 1978, which resulted in a string of intrigue, murder and cruelty that I’m surprised People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, or PETA, doesn’t include as a header on their website. The first few rams (all named Rameses, an indication of the failing dynasty to come) were kidnapped and met their ends in slaughterhouses. The exception was Rameses III, who was reportedly extremely aggressive, escaped several times and interrupted local train schedules until he had to be ceremonially executed by the Fordham Rifle Team.

As a university in the middle of New York City, we simply don’t have the facilities or the staff required for the upkeep of a live ram at either campus.

I won’t give a full bloody history of the rest, as I wouldn’t want to rob someone of a compelling and frankly horrifying book idea, but honorable mentions include Rameses XVIII, whose shed was burned down and who later died of alcohol-related liver disease; Rameses XXI, who was kidnapped so often he spent more time at rival schools’ campuses than at ours; and Rameses XIX, who was dyed green by Manhattan College students and died after a long battle with the flu, running up steep medical bills for Fordham to pay.

While this might make one wonder if animal cruelty was the only other pastime before the invention of cable television, I wouldn’t devote such an optimistic outlook to the present, either.

I enjoy most of the people at Fordham. But, I don’t find that mutually exclusive with the fact that in every group of co-eds I’ve ever been in, there’s someone who gets intoxicated and does something unspeakable for Snapchat, and then everyone has to live with it. (One time I saw a drunk young man kick a pigeon, and I still think about it every day.)

It would only be a matter of time before a student hurt the ram— by dyeing it, taking it to their dorm, trying to feed it a Rice Krispies Treats and killing it instantly. How would a lone ram defend itself against college students returning from a night out?

There are facilities and student programs that deserve the attention and money that would go toward this lone ram.

Any live animal deserves a proper habitat and adequate care to ensure its well-being. As a university in the middle of New York City, we simply don’t have the facilities or the staff required for the upkeep of a live ram at either campus.

Even if livable conditions were established, we would have to consider the cost of crafting a biome for a single ram in Manhattan or the Bronx. I assume ram food costs money, and I can’t imagine any field crops would thrive on Fordham’s campus, especially at Lincoln Center.

Fordham’s monetary distribution is questionable at best, and the university community is already frustrated by the 6% increase in tuition for next year. I don’t think that — considering the list of things that need financial attention — getting a live animal to just hang out should be a top priority. There’s brown mold in my dorm right now as I write this. (Seriously, anyone reading this, please help with the mold in my dorm.)

There are facilities and student programs that deserve the attention and money that would go toward this lone ram. Would it be cool to walk around campus and turn to see a farm animal? Maybe, yeah. Every time I’m on a road trip and I see cows, I yell “Cows!” But they’re on a farm, where they’re supposed to be. As much as I might love to yell “Ram!” multiple times per day, it would be unfair to the animal. Sometimes I even feel bad for the squirrels who live at Rose Hill. I know there’s a better life waiting for them somewhere. I couldn’t imagine the dismay I would feel seeing a real ram. They have big eyes and look sad at the best of times.

Any gratification I might get from seeing a ram would be for me, not the ram. He wouldn’t be happy to see me. He wouldn’t even know me. I wouldn’t want to condemn him to an existence on a college campus. Even if he only shows up at the football field and the basketball courts, his presence would solely be for the benefit of the students. The ram doing a lap at halftime might be a nice Instagram story, but it would undoubtedly be a harrowing experience for it. Besides, the Rameses mascot, that genius in a suit, would be out of a job. They walk on two legs and can make people do the wave. No animal can do that.

I’m not a perfect person. I’m only vegetarian 75% of the time. But I could not, in good conscience, support trapping a ram in a life of watching overcaffeinated college students vape in the quad — not after all we’ve done.