The End of an Era: ICP Memorializes the Contact Sheet

February 22, 2012

The contact sheet, similar to the horse-drawn carriage or music stored on a disc, is enigmatic in today’s world. Technology has advanced; we have new, more efficient ways of doing things. Yet these objects are still around us, not because we need them, but because we refuse to let them go. As a culture, we still admire what these artifacts stand for.

The contact sheet is tied to a form of photography that is making way for the digital age. Only a few weeks ago, Eastman Kodak, the company whose name is synonymous with film photography, filed for bankruptcy largely because demand for film has nearly vanished. Now that shooting a roll of film has vanished from the mainstream, the contact sheet, a way of reviewing all of the frames on a roll at once, is going with it.

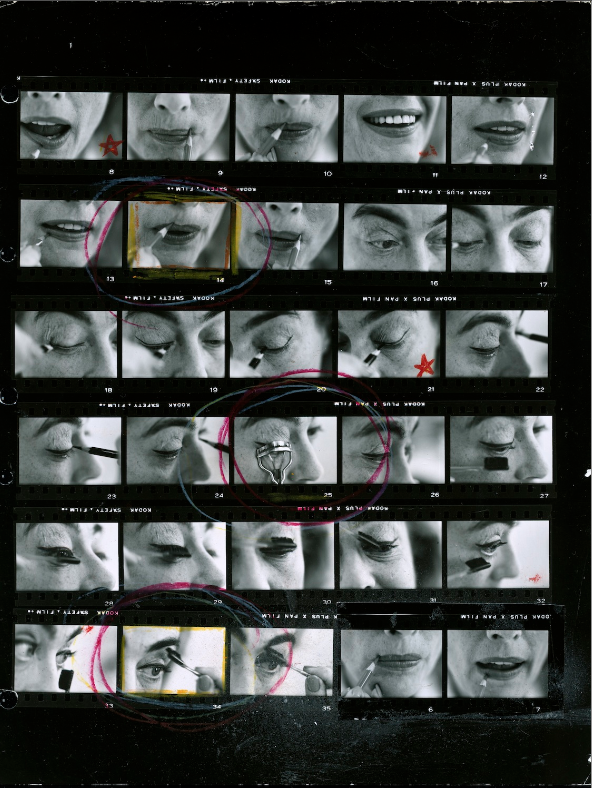

Physically, a contact sheet is a set of images from a roll of film printed next to each other, allowing the photographer to easily compare them and pick out the best shots. But more than that, the contact sheet is a way of viewing the artistry and meticulous effort that is put into expertly capturing a moment on film.

At the corner of 43rd Street and Avenue of the Americas, the International Center of Photography (ICP) is housing an exhibit dedicated entirely to these relics of the film age. The show, titled “Magnum Contact Sheets,” displays a selection of these prints made by Magnum photographers from the 1930’s onward. The exhibit is both a memorial to this antiquated method and a celebration of its fringe survival because of the work of dedicated film photographers in a digital age.

As ICP Associate Curator Kristen Lubben sees it, “The contact sheet embodies much of the appeal of photography itself: The sense of time unfolding, a durable trace of movement through space, an apparent authentication of photography’s claims to transparent representation of reality.”

Wandering the exhibit gives an intimate look into the creative process that spawned many of the most iconic photographs ever shot. One such photograph is Philippe Halsman’s portrait of the surrealist painter Salvador Dali. The image captures the painter, furniture, several cats and a stream of water all suspended in midair, and to this day, remains instantly recognizable.

The contact sheet tells another story that is impossible to tell in a single frame. Instead, the sheet documents the hours of painstaking effort that went into capturing that sublime moment in a single image. On the contact sheet, the viewer can see some photos that were shot too soon, me too late. In a few, Dali’s face is blocked by a flying object, rendering the shot useless as a portrait. In others, we can see the arm of an assistant creep into the frame.

By looking at all of these frames simultaneously, we are able to get a much more intimate grasp of Halsman’s creative process. Because of this, “Magnum Contact Sheets” is as much a celebration of the photographers as it is of the work that they were able to produce.

The contact sheets allow us to glimpse the chaos of war through the lens of Robert Capa’s camera as he photographed the first wave of the D-Day invasion. They let us sit down with Che Guevara for an afternoon, watching his cigar dwindle, just as Rene Burri did in 1963. They let us view these and more moments, not as single frames, but as stills from a greater narrative. Each sheet has a different story to tell. The exhibition will run until May 6.

IF YOU GO

Magnum Contact Sheets

When: Now through May 6

Where: International Center of Photography, 1143 Avenue of the Americas (at 43rd Street)

Price: $8 with student ID, voluntary contribution Fridays from 5 to 8 p.m.

View International Center of Photography in a larger map