The Kids’ Table

November 16, 2011

I heard the familiar clank of Grandma’s cane slapping against the concrete hallway floor all the way from the living room couch. She burst through my parents’ perpetually unlocked apartment door, and with little regard as to who was in the room, she dug into her bag and yanked out a birthday card and a plastic sack of about 500 NYC-brand condoms and tossed it on my lap.

“Es good for the AIDS. Happy bieerthday, Boo Boo.”

“Es very good for the AIDS,” I responded in my Spanish-English hybrid that consisted of the 20 Spanish words I know. “Gracias, Abuelita.”

Looking up, I noticed that my oldest brother Lou and his new girlfriend Patti were staring at my pragmatic new birthday gift in horror. Before he could conjure an explanation for Patti, Mom quickly shuffled over in her cleaning frenzy, picked up my condoms, and without any thought, neatly arranged a handful in a cute antique tin for the bathroom. “Fucking 500 condoms, like the kid is some stud,” Mom muttered as she ran to the bathroom, placing the tin of contraceptives right next to the hand soap and the toilet paper. Patti looked mortified. I assured her that if she could make it until Grandma started passing out pre-dinner Xanax like party favors, she’d make it through her first Nuñez Thanksgiving.

My 21st birthday was the next day, so we were celebrating it during Thanksgiving dinner. Instead of being with my friends and college roommates, I was stuck with my family for the occasion. Each year, Mom’s side of the family—the Puerto Rican side—gathers at the spacious apartment in the basement of a fancy Upper West Side building that my father is given for being the superintendent. Every year, my parents swear that they will not host another year of rowdy Puerto Rican relatives. We all know that they will, but we stay quiet and let them think that one day they’ll be liberated from their hosting duties.

The usual relatives started funneling in one at a time: Aunt Eva (or “Eva the Diva” as I call her) and her husband Ray, Uncle Angelo (who was never that sharp but has really been off since a six-month coma that followed a car accident some years ago) with his daughter, and my two older cousins and their husbands. Once the ladies converged in the living room, they formed what I call “the Semi-Annual Council of Ailments and Suffering.” One of the women, usually Grandma or Eva the Diva, will begin to complain about her arthritis, and everyone else in the council will try to top it with sob stories of her own medical woes. The council then concludes with a short bragging session about how great each of their rheumatologists is and an exchange of prescription medications that the FDA would frown upon.

When it came time for the family to be introduced to Lou’s new girlfriend, I became almost as tense as my brother. Sure, she wasn’t my girlfriend, but I already knew the kind of judgmental glares my brothers and I could expect once my relatives started querying Patti about her Orange County upbringing. Lou carefully navigated the conversation around topics that probably made Patti equally uncomfortable—where she was from, what her parents do, where she graduated from, etc. But there was nothing he could do about how she looked. Patti dressed with the style, class and ease that were synonymous with a privileged background, and everyone could tell. Her polite and unpretentious demeanor made her likeable to our relatives, but there was no way she could know how closely she matched the long-standing stereotype our relatives had of us.

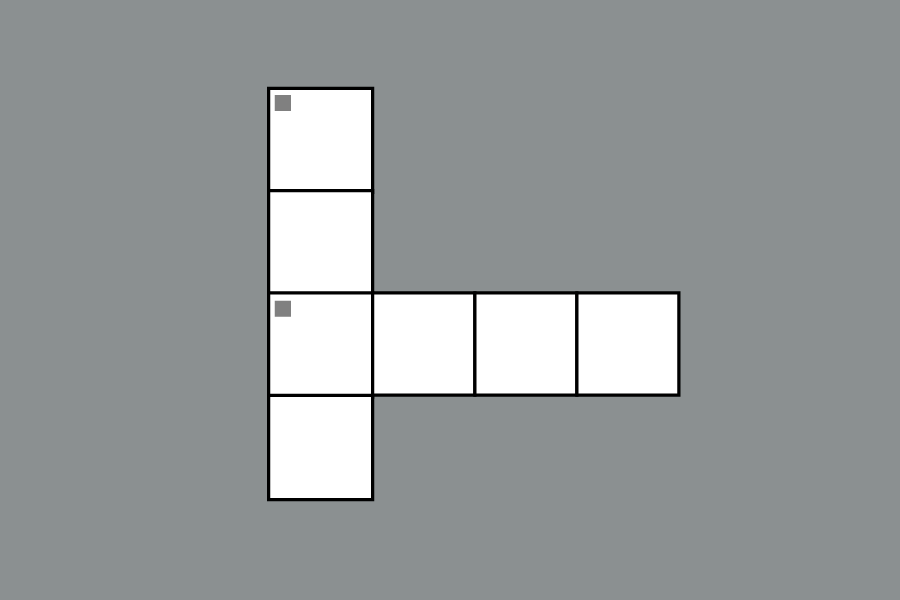

I thought we were out of the woods as we sat for dinner at our respective kids’ and adults’ tables. Then, suddenly, the stinging phrase that has been pounded into my head by my relatives for years was finally uttered for the first time that night:

“Yo White Boy, now that you’re all grown up, you’re finally gonna go to a strip club or what?”

White Boy. That’s what Uncle Angelo had called my brothers and me since we were kids, and though he was always first to say it, he wasn’t the only one thinking it. My brothers and I were the only members of Mom’s side of the family not to be raised in or around the projects. We grew up in a huge apartment without having to pay rent or utilities because of Dad’s job. We never had to worry about getting mugged in the elevators late at night or being shot outside of our front door. We went to private schools with all the money my parents saved on rent, and we learned proper manners and social skills from observing the people in our neighborhood. We never learned Spanish because my parents were too busy working to teach us, and our only real connection to Puerto Rican or Latino culture was through the food on our Thanksgiving dinner table. As we grew older, we started to identify with our Puerto Rican and Cuban roots almost in a satirical way; I was even beginning to become embarrassed to identify with the ghetto Latinos I had seen near my relatives’ project buildings.

Our relatives always told us that we three boys were the smartest in the family. They were quick to brag to friends and co-workers about what high schools and colleges we attended. My two older cousins were cheering louder than anyone in St. Patrick’s Cathedral when I graduated from high school, despite having received their diplomas in small, run-down school churches. Everyone who knew Eva the Diva had heard that Lou was going to be the first person in our family to go to law school. To the outside world, they were as proud a family as anyone could hope for. But here, at the Thanksgiving table, we were treated differently. We at the kids’ table were kept at an arm’s length.

I ignored Angelo’s question about the strip club and listened to my relatives at the adult table. Uncle Ray bragging about a new stereo system he had installed in his used Mercedes Benz while simultaneously griping about life in the projects. Angelo still brandishing his 1960s Latino machismo after two debilitating knee surgeries. Eva reassuring herself that her knock-off Coach bag looks just as good as the real thing. All just noise to an outsider.

Dad came out with my birthday cake.

“Where do you want it?” he asked.

“There’s no room here,” Mom replied. “Put it on the kids’ table.”