Fordham’s History of Gentrification

The university needs to take accountability for its past and educate students on how to create a better future

TDORANTE10 VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The recently renamed Robert Moses Plaza signifies a deep history of Fordham’s gentrification and displacement, which must be acknowledged and rectified.

April 28, 2022

Maybe it’s because I was born and raised in the Midwest, but I had never heard the name of Robert Moses until Aug. 27, 2021. I was in a hotel room in New Jersey, finally completing some readings for Urban Plunge, a service-based pre-orientation program at Fordham.

As I read about New York’s history of discrimination and about the communities kicked out of their homes to make way for Fordham’s Rose Hill and Lincoln Center campuses, I realized that I had naively assumed Fordham did not have the same flawed past as other universities. I later discovered that many of my peers are unaware of Fordham’s history of uprooting low-income communities of color.

Fordham needs to be more upfront and apologetic about how it has harmed certain communities in the past, and the university needs to incorporate more information about its history and harmful legacy into its education.

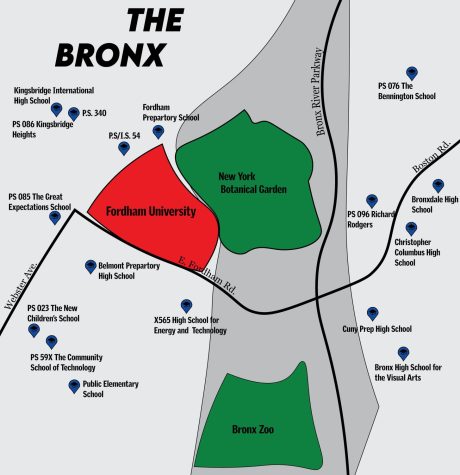

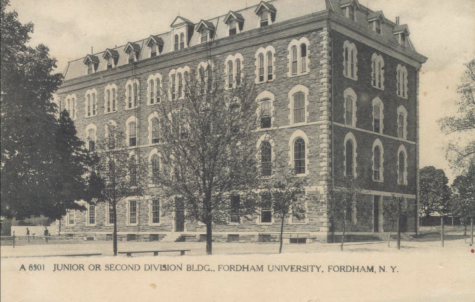

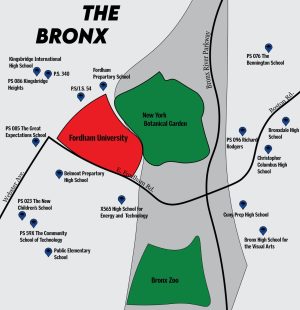

Before either Rose Hill, Lincoln Center or even New York City were established, the land that both campuses are on belonged to the Lenape Tribe. The Lenape first encountered colonizers in the 1500s and they were later taken over by the Dutch in 1626. The neighborhood of Fordham in the Bronx was established in the 17th century by Dutch settler John Archer. In 1751, he built Fordham Manor on land that is part of modern-day Rose Hill.

This history of the Lincoln Center campus is also one of displacement and gentrification.

In 1838, the Bishop of New York, John Hughes, bought 100 acres of land, constructing St. John’s College over the next two years. St. John’s College was sold to the Jesuit Order in 1846 and became Fordham College at the start of the 20th century when two graduate schools opened and the entire institution became Fordham University.

The land that Fordham was established on is stolen land, and the university continues to gentrify the surrounding areas. For example, more than half the neighborhood of Belmont in the Bronx utilizes welfare assistance while most students have financial guarantors that guarantee payments. This leads to rising rates of rent in the area as students populate it, pushing out those who lived there first.

This history of the Lincoln Center campus is also one of displacement and gentrification. As Robert A. Caro lays out in his book “The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York,” when Moses was planning his Lincoln Center Title I development, he was already displacing tenants from acres of real estate. Fordham University wanted to purchase more land and expand the university, but it could not afford the expensive cost of land in Manhattan.

Moses displaced hundreds of people to provide a generous six-acre gift to the university.

As the chairman of the Slum Clearance Committee, Moses displaced hundreds of people to provide a generous six-acre gift to the university. The university has grown since then, and the plaque honoring Moses in what was formerly known as the “Robert Moses Plaza” was moved to storage in 2016 and has not been returned since.

This is a short snippet of a complex and nuanced history, which is why more information on Fordham’s legacy should be provided for students. Part of Fordham’s mission is to connect with the community around us, and learning about our history within that community is vital. I learned about the history in a pre-orientation program, but it should be added to the full-school orientation as well.

Another way Fordham could implement teaching students its history is to add an attribute to the core curriculum to address Fordham’s history and its obligations to surrounding communities. Fordham already has an extensive core, and it would be easy to fit the university’s history into it. Alternatively, it could be a required topic to cover at least a reading or two in the first-year English requirement, English Composition II. More history classes could also be added that tackle the history of New York City.

In the ongoing conversations about what obligations urban universities have to the communities around them, education of university members is an important first step. It cannot be the only step — because education without action isn’t helpful — but it is a good place to start.

The issue of elite colleges taking land from disadvantaged communities extends beyond the gates of Fordham. The communities that house urban colleges are often underserved, with wealthy private institutions placed in the middle. Recent violence at the University of Chicago and Manhattan’s own Columbia University should also lead Fordham students, and especially the university, to reflect on their roles of support in the communities they occupy.

There is a dire lack of mental health and other resources in communities surrounding urban colleges such as Columbia, and even though they donate “undoubtedly a large sum of money, it pales in comparison to the ways in which the city might gain if Columbia were taxed in a manner more aligned with the private sector,” according to the New York Times.

Many urban college campuses continue to pose problems for the communities surrounding them centuries after their incorporation.

Since the sweeping racial justice movements of 2020, more Americans have begun to examine how institutions, like universities, are complicit in reaffirming and maintaining racial inequalities in American society. For example, the history and twisted legacies of the Ivies received renewed attention as a result of these movements. These prestigious schools were founded by slave owners and built by slaves. Even now, the effects of this history can be seen in various aspects of higher education, from acceptance and enrollment gaps to how locals feel about students “invading” their communities.

In addition to uprooting existing communities, many urban college campuses continue to pose problems for the communities surrounding them centuries after their incorporation.

A grievance that is heard throughout New York City, especially during the beginning of a new academic year, is how “annoying” NYU students are to the city. Native New Yorkers complain that they can always tell when the new NYU students have moved in because local spots are crowded with disruptive first-years. I’ve even heard Fordham students criticize NYU students for the same reasons, saying they are glad that they are not associated with those students who don’t fit in with the locals.

While Fordham is one of the higher-ranked universities in NYC, it is nowhere near as famous (or, rather, infamous) in other parts of the country. This lack of recognition is a reason why Fordham has not faced as much public scrutiny and, at times, unapologetic hate as other, larger universities. Though not spoken about as much, Fordham does have a flawed past that needs to be understood by its students.

No matter how Fordham proceeds, we, as a university, must begin to acknowledge the harm that our school has done in the past and perpetuates to this day. Only then can we start to take action to right the wrongs committed by our university.