Why You Should Be Glad Fordham Doesn’t Have Greek Life

The Delta Delta Delta variant’s toxic effect on college campuses

September 9, 2021

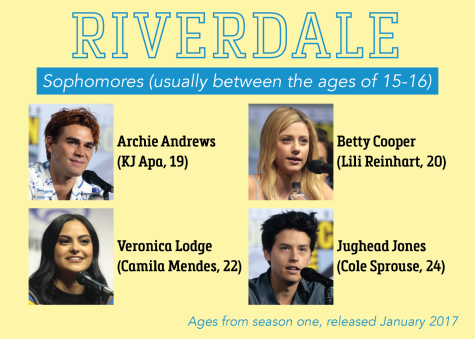

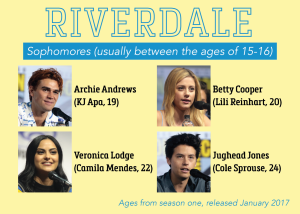

The end of summer means you’ll be seeing viral Outfit of the Day videos and creepy door chants flooding your social media feed from students rushing Greek life organizations. As a Jesuit college, Fordham University doesn’t have a Greek life scene. Some students may undoubtedly feel they’re missing out on the “traditional” college experience, and the glamorized houses, parties and friendships.

However, what viral TikToks and Instagram posts don’t show are the ugly sides to Greek life, such as the expensive dues, the safety risks and the discriminatory practices with which historically white social Greek letter organizations are associated.

In reality, the Greek life tradition should not be indicative of what a normal college experience in the United States is supposed to look like, but should instead be seen as a dangerous curse, the continuation of which is harmful to college students.

The Hazing

Insiders and outsiders alike of Greek life know one thing about the recruitment process: prospective new members are often hazed before they can join an organization. This is usually justified by Greek organizations as building brother/sisterhood or through claims that hazing is just doing menial tasks and is harmless fun. However, hazing in practice is often much more serious.

While every organization is different, some members have described being forced to “simulate oral sex with cucumbers,” “bring bathing suits and magic markers and falsely being told that sisters would circle body fat on new members,” and “sit in a kiddie pool filled with rotten food and excrement for hours.”

Although most universities and chapters have anti-hazing regulations and hazing is a crime in many states, this hasn’t stopped the practice.

They were the lucky ones. There have been over 50 hazing-related deaths since 2000 in colleges across the country. Oftentimes these deaths are related to heavy drinking, but official causes of death have included head injury, heatstroke and cardiac arrest. What has been labeled as a “right of passage” has been recreated year after year in a traumatic and sometimes fatal experience. Because of Greek organizations’ strict policies against sharing what happens during rush, most stories go unreported.

Although most universities and chapters have anti-hazing regulations and hazing is a crime in many states, this hasn’t stopped the practice. Rather, it has encouraged students to remain silent for fear of legal repercussions for their chapter and their “friends.” No social organization is worth the lives of dozens of young people and considering how important hazing is to the Greek experience, it may be time to give the idea of abolition serious consideration.

Still, some argue that hazing is only an issue when recruits first seek out membership in a Greek organization, but Greek life often puts their members and their communities at risk throughout the school year.

Community Health and Safety Risks

Greek life is associated with a culture of sexual assault. According to The Guardian, fraternity brothers are three times more likely to rape than non-fraternity men, and sorority women are 74% more likely to experience rape than non-sorority women. Recently, the Phi Gamma Delta chapter (also known as Fiji) at the University of Nebraska Lincoln campus was suspended after students protested the fraternity’s presence on campus due to an alleged assault that took place on the first day of classes.

University officials’ refusal to outright ban the fraternity and the fraternity’s casual and mocking tone toward the protests demonstrates how normalized sexual assault has become in Greek letter organizations.

Hundreds of students gathered outside the Phi Gamma Delta house for several nights in a row, and students claim to have received via Airdrop a video from fraternity members inside the house of brothers laughing and making fun of protesters. Many students are calling for the fraternity to be banned from campus, especially since this is not the first time the fraternity has been suspended.

Student protests represent a change in the culture surrounding Greek life; however, university officials’ refusal to outright ban the fraternity and the fraternity’s casual and mocking tone toward the protests demonstrates how normalized sexual assault has become in Greek letter organizations.

Students aren’t only at risk of being attacked or hazed when they join Greek life, but also of getting sick. Many Greek organizations have been accused of causing COVID-19 outbreaks on their campuses. Last winter, Chi Phi at Lehigh University allegedly hosted “COVID parties,” at which students who tested positive for COVID-19 or who had already been exposed to the virus were invited.

Needless to say, Greek organizations tend to attract students of middle- or upper-class standing.

Unsurprisingly, the party culture and lack of regulation associated with Greek life have extended to the COVID-19 crisis, demonstrating some organizations’ lack of care for the general well-being of their campuses and surrounding communities and a belief that they are above the rules — both written and social.

Going Greek or Going Broke?

Many Greek organizations are the most secretive about one thing in particular: dues. Although most chapters urge their members not to share this information, dues can range from anywhere between a few hundred to a few thousand dollars a semester. This does not include the cost of living in a sorority or fraternity house if a student chooses to do so or the costs associated with fundraisers, gifts for other members, new clothing and other social obligations. Needless to say, Greek organizations tend to attract students of middle- or upper-class standing.

It’s All Politics

So where does the money go? Most of the money contributes to paying national conference dues, national chapter dues, insurance for the chapter and costs associated with running the individual chapter and its social events. But some organizations dip their hands into politics and donate to the Fraternity and Sorority Political Action Committee, also known as FratPAC.

FratPAC claims to be a bipartisan organization that seeks to “amplify the benefits of the fraternal experience for students,” however, it does so by advocating against strict hazing laws and for tax loopholes for Greek-owned houses and laws that strengthen the due process rights for alleged sexual assault offenders, potenitally making it harder for victims to come foward. Although the organization claims to be bipartisan, the majority of its funding goes to Republican candidates, with its largest contribution in the last election cycle going to Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell.

For some colleges, Greek organizations can play an even greater role in school and local politics.

For some colleges, Greek organizations can play an even greater role in school and local politics. At the University of Alabama, “the Machine,” an underground organization of fraternities and sororities secretly determines how students should vote in the student government and even local school board elections. From 1986-2015, no student government president was elected without the Machine’s support. The group allegedly terrorized non-Machine candidates, specifically African Americans, by putting burning crosses in their yards, threatening them and their families, and even running a campaign member off the road.

The group has also been accused of pressuring Greek students into voting a certain way by bribing them with free drinks and limo rides and of using these practices to swing local school board elections. Although the University of Alabama has never formally acknowledged the Machine’s existence, the school’s newspaper published a timeline of the Machine’s alleged activities in a magazine for new students. Considering the political impact of Greek letter organizations, it is worthwhile to examine the historic makeup of these groups.

A Hateful Past

Greek letter organizations were historically created by upper-class white students on the basis of excluding others, and this practice still exists today. Many students have shared their stories of racist encounters while participating in Greek organizations, leading some chapters to disband entirely.

The continued homogenous presence of Greek organizations rests in the rush process. Former members of sororities describe ranking potential new members based on appearance and how much they look like the rest of the group.

Greek organizations actively discriminate in their recruitment process.

In 2010, 77% of sorority members at Princeton University were white, and fewer than 10% were from middle- or lower-class families. Greek organizations actively discriminate in their recruitment process because discrimination was built into their founding. Recruitment has always been this way, and with groups disbanding rather than attempting to reform the system, rush cannot exist without racism and classism.

Why Go Greek?

So why are students still joining social fraternities and sororities? And why do so many colleges let them run free on campus? For one thing, Greek organizations can justify their existence through philanthropy. Social Greek organizations need to devote a certain amount of money and time toward a specific charity.

Every chapter differs in how much they prioritize charity, but looking at Yale Greek life, most organizations raised a few thousand dollars for charity despite each member paying at least $350 in fees and chapters paying for other lavish expenses. Although there is nothing inherently wrong with charity, nonprofit work in Greek letter organizations is not important enough to the Greek experience to justify organizations that continue to harm thousands of young people every year.

Many argue that Greek life provides networking opportunities for the rest of a student’s career, and it is true that 85% of Fortune 500 CEOs were in fraternities, as were 76% of all current congressmen and senators. It is worth questioning whether a person’s Greek affiliation is what made them successful, or if it is their privileged position as a white, wealthy educated person that helped them obtain a spot in Greek life that also allowed them to be successful in their careers.

Starting college is one of the most terrifying and isolating experiences in a young person’s life.

While networking may exist in the Greek community, it is not the pipeline to success it claims to be. Philanthropy and networking are sloppy excuses for what Greek organizations are really providing: parties and a sense of community.

Starting college is one of the most terrifying and isolating experiences in a young person’s life. A community of close-knit friends who always know where the parties and cool events on campus are seems like a dream, even if you do need to pay and jump through some hoops for membership. Greek organizations are fueled off of vulnerable students joining, whether they’re freshmen away from home the first time, sophomores who haven’t seen a “normal” campus yet or anyone else who feels like they don’t belong.

These organizations prey on vulnerability, and once students are upperclassmen, they continue the tradition, exerting their newfound power on students who are now in the position they were in a few short years ago. Colleges let these organizations stay on campus because it is a social expectation for many, a draw to the school for others and most importantly, a must-have for Greek alumni — who, again, tend to come from privileged backgrounds and who tend to be some of the biggest donors to the school.

Without Greek life, Fordham students do not have to worry about hazing or fitting in with a popular crowd of students.

Greek life is enticing for colleges and students alike, even though it creates a toxic campus environment in most cases.

Despite not having Greek life, Fordham does exhibit some of its toxic traits. In a survey conducted by the Observer last year, 90% of students said that they believe discrimination is present at Fordham. Greek life is of course not the only racist, elitist factor on college campuses, and colleges like Fordham must make a serious effort to change their past. Even though Fordham is far from perfect in terms of equality, it is a better campus community because of its lack of Greek life.

Without Greek life, Fordham students do not have to worry about hazing or fitting in with a popular crowd of students. And even though Fordham is not innocent in preventing all discrimination, an organized collection of students who perpetuate discriminatory behaviors would undoubtedly make Fordham much less inclusive. First years, don’t ponder on what might have been if you had gone to a different college, but instead, be glad that Fordham is protecting you from a toxic, unnecessary tradition.

Rafael Matos • Jan 1, 2022 at 1:45 pm

As a member of a fraternity, I recognize and agree there a variety of issues that make fraternity and sorority life, at times, problematic at best. I think our organizations have a lot of work ahead to make some things right. While I appreciate your candor, I am also concerned by the way you presented your facts. I do not dispute the claims you made in your article. I do, however, take issues with presenting information that only supports the perspective you want to promote, that Fordham University is better off without fraternities and sororities because of the issues created by one section of the overall fraternity and sorority community.

The incidents you described were committed by historically White fraternities and sororities. You generalized these acts in a way that makes them reflective of all fraternity and sorority life. In doing this, you centered Whiteness and erased the existence of fraternities and sororities founded to create communities that serve, support and protect individuals with marginalized identities.

For example, you do not make mention of historically Black Greek-letter organizations (BGLO), inclusive of fraternities and sororities, that were founded to help (primarily) Black men and women persist through college and beyond their collegiate experience, well into alumni life. Your piece does not mention BGLO’s significant contributions to advancing civil rights in the United States.

I believe the written word is very powerful and you have a responsibility as a writer to provide actual and factual information of relevant perspectives involved, not just data that supports the side you favor. As I mentioned at the start of my comment, fraternities and sororities have issues we have to address and eradicate to be in better alignment with the vision our respective founders set from our respective beginnings. I believe this should be done in a manner that addresses the central issues without marginalizing community members.

I am open to help you gain further understanding of the fraternity and sorority community as a whole and the multiple communities that exist within the larger group.

E.R. • Sep 11, 2021 at 1:03 pm

so true bestie!! great piece!