Whom Is Instagram Activism Really Helping?

We should amplify the voices of marginalized communities, not reduce them to a one-sentence graphic

December 8, 2020

We should amplify the voices of marginalized communities, not reduce them to a one-sentence graphic.

We should amplify the voices of marginalized communities, not reduce them to a one-sentence graphic.

The Thursday before last was arguably America’s most problematic holiday: Thanksgiving. At this point, I doubt there is a single 18- to 30-year-old college student out there who can’t point out the issues behind celebrating the history of this day. Yet, my Instagram feed of almost entirely 18- to 30-year-old college students is hell-bent on sharing posts, graphics and cutesy art explaining why Thanksgiving is an issue.

Of course, that’s completely valid, because Thanksgiving absolutely has roots in Indigenous genocide. But I can’t help but ask myself: Whom are these posts really for? There must be a better way for allies to actually help the people affected by the issues outlined in these surface-level, PSA-type posts.

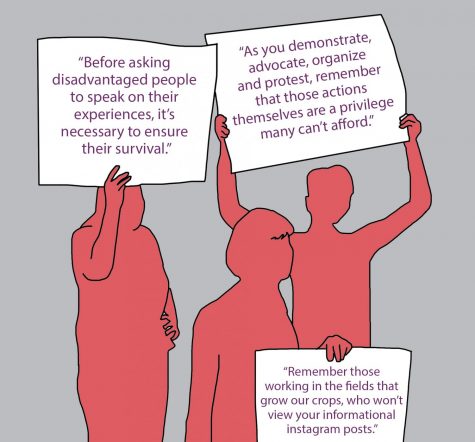

Before I go down this road, I want to point out that some of the political activism content I see on Instagram is great and very informative. However, the majority isn’t. Half of the time, no actual information is being offered at all — there’s just a short, aesthetically pleasing message ironically juxtaposed against a grave and often life-or-death issue. If you’re lucky, there will be a link to donate funds to the parties in need of assistance, but that isn’t always the case.

Most people who advocate for social justice do not keep racists, homophobes or climate change deniers as followers.

I’ve definitely shared these unproductive posts before because, in sharing, it’s easy to feel like you’ve done something to help. But it’s time for us to have a conversation about why “spreading awareness” only helps so much, and why we should be more thoughtful about the activism we endorse.

The first problem with this type of social media activism is the audience. Personal social media accounts generally tend to not have a wide audience, but the real problem is that they don’t have an ideologically diverse audience. Most people who advocate for social justice do not keep racists, homophobes or climate change deniers as followers.

This is understandable. But the people who actually need to see the information about combating oppression aren’t getting access to it if that information is only shared online in communities with similar ideas and similar access to resources. If you really want to make a difference by disseminating information, share it on Facebook among all of your ideologically distant family members or, even better, call out the oppression in your own community.

A big problem that arises when social justice media is shared among these echo-chamber-style social circles is that people start to get comfortable. They think that because they and their friends shared a cute graphic on something they all already knew anyway they have accomplished some type of activism. But there is no power in empty repetition.

The creation of Black Lives Matter into a social media trend, for example, has definitely hindered the movement’s progress. People repost the words so often that it seems they forget what they stand for, and as a result, an extremely powerful and radical movement becomes a mere hashtag.

The meme-fication of Breonna Taylor’s death was proof of this fact: Social media amplification doesn’t help an issue if it’s done badly. People in “woke” circles added Breonna Taylor’s name to everything, likely with good intentions, but with the result of distracting from the reality that a beautiful young woman was murdered in cold blood. Thus, repetition under the guise of awareness leads to desensitization.

For them, advocacy becomes an indicator of social status because it’s not life or death.

So why are people turning complex issues into trendy little posts? I would say that the majority of the people doing this do not have bad intentions. People want to feel like they are doing something because silence is the worst course of action, after all. Particularly, white, well-off, liberal students may feel as if they have to compensate for their privilege, and the Instagram repost is the easiest way for them to do so. In turn, they scrutinize the advocacy of their friends, criticizing those who don’t participate in the same empty activism. For them, advocacy becomes an indicator of social status because it’s not life or death. So it doesn’t matter if it’s done right, just that it exists.

I would be remiss to not give credit to the good content. Posts with genuinely helpful information on supporting the businesses, dreams and basic existences or marginalized people are a valuable resource. This Thanksgiving, among the decorative and performative “Thanksgiving is bad” posts, I came across one filled with Indigenous creators to support. I promptly spent the next thirty minutes admiring beautiful art and planning my Christmas gifts around it. I saw another post that had a link to a resource that could tell you the name of the Indigenous land you were on, and one promoting Indigenous activists, expanding the reaches of their voices rather than attempting to speak for them in a one-sentence graphic.

This is the energy we need to keep in all of the issues we advocate for. It takes little effort to consider the purpose and efficiency of a shared post. Is this post to make you yourself feel better? Or is this post going to help someone who needs it? You decide.