It Cost Me $13,860 to Vote

The naturalization process to become an American citizen

The naturalization process is long and expensive, making voting in the United States a privilege that is not accessible to everyone.

October 28, 2020

I turned 18 less than a month before the 2016 presidential election. I could not vote; neither could my parents. Despite living in the United States for almost 20 years, we weren’t citizens yet.

The right to vote — especially in this year’s election — was a major motivation for me to go through the naturalization process. However, finally becoming an American proved to me that voting in this country isn’t a right — it’s a privilege.

My family moved from Manila, Philippines, to St. Louis, Missouri, in 2000 when I was only two years old. My parents came to the states on the H1-B program, a work visa that allows U.S. companies to hire nonimmigrants for “specialty occupations,” jobs that require specialized theoretical or technical knowledge. My dad’s work was opening a U.S. office and they needed an architect.

In 2008, my fourth grade class had a pretend election and my classmates voted how their parents were voting. (Mostly McCain — it was a Catholic grade school in Missouri, after all.) When the ballot written with crayon came to my desk, I said, “My parents aren’t voting; we’re not citizens.” My teacher asked me in front of the whole class, “Are you legal?” This was the first time that I was ashamed of being born in the Philippines; I was embarrassed. I went to the bathroom and cried.

In the wake of our new presidency in 2016, our immigration lawyer urged us to apply for citizenship — “We just don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Naturalization — becoming a United States citizen — is a long, grueling and expensive process. My parents’ H1-B petition cost $3,460. After two years, H1-B visas qualify for renewal or a Green Card application, permanent resident status.

The journey to receiving my ballot took two decades and cost roughly $13,860, give or take a few Southwest flights. Triple that to account for my parents.

Filing for a green card includes $1,925 application and filing fees and a $250 medical exam. As a permanent resident, you can legally work and live permanently in the U.S. You need to live in the U.S. for five years before you can apply for naturalization. The application fee for citizenship is $725, non-refundable. According to our family lawyer, legal fees can amount up to $7,500.

After submitting the application, we had to go to a biometrics appointment to submit fingerprints and then an interview with an immigration officer where we tested our U.S. history knowledge and English skills.

I went through this process from Nov. 2018 to Sept. 2019 — after spending nearly my entire childhood in this country, it took nearly a full year to prove that I was American. Although we had become residents years before in 2008, we had to save up money since it was the recession, and my parents were starting a new business.

I flew back and forth from New York to Missouri four times throughout the process.

The interview was the scariest part. My mom insisted I wear a dress and put on makeup, to “look nice, so they’ll respect you.” It’s the same thing she tells me when we go to the airport. At the immigration office, I was asked if my mom could speak English (her first language) by every officer.

I learned the majority of the interview questions in seventh grade social studies, and my dad knew the answers from watching the History Channel every night, but my mom had to cram by watching quiz videos on YouTube.

I only remember one of my questions — “Who is the Speaker of the House?” I had to read aloud “Where does the President live?” and write out, “The president lives in the White House.” I had to legally swear I was not a Communist.

My oath-taking ceremony took place on Sept. 6, 2019, at Harris Stowe University. I sat behind a woman from New Zealand in the auditorium. It felt like a graduation, but our diplomas were our citizenship certificates. We sang “America the Beautiful” and had a guest speaker.

In front of the District Court of Eastern Missouri, I had to recite the Oath of Allegiance, which entails swearing to defend the Constitution against all enemies, renounce any fidelity to any foreign state, bear arms on behalf of the U.S. and promise to perform noncombatant services for the Armed Forces when required by law. If I was male, I’d be registered for the Selective Service.

As a right, voting should not be exclusively accessible only to those financially privileged enough to go through naturalization.

The (literal) American starter pack includes a mini-flag, a pocket Constitution, a flyer of all my new rights and freedoms and a letter from the White House that said “This American legacy is now your legacy. This history is now your history,” signed by Donald J. Trump.

My life hasn’t changed at all since becoming a citizen from a permanent resident, except I stand in a different line at the airport, and of course, I can vote.

The first thing I did was go to the League of Women Voters of Metro St. Louis table and register. I will be voting in-person on Nov. 3 for the first time, as it’s now my right.

Paying the Price

The journey to receiving my ballot took two decades and cost roughly $13,860, give or take a few Southwest flights. Triple that to account for my parents. However, citizenship was not the only thing standing in my and many others’ way of voting.

As a right, voting should not be exclusively accessible only to those financially privileged enough to go through naturalization or, for the natural-born, take significant time off of work and school. Filling out a ballot is a privilege.

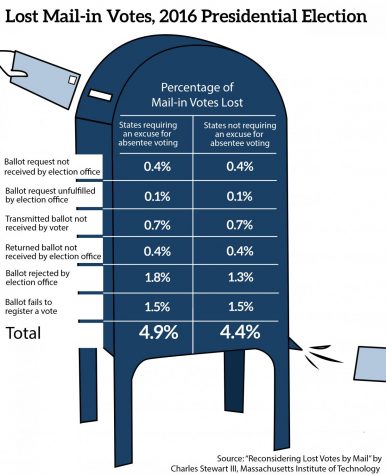

Voter suppression is rampant in the U.S. A 2019 study by Cornell showed that those in line at polling sites in predominantly Black neighborhoods wait 29% longer than those in predominantly white neighborhoods. Absentee ballots are not being delivered in time and rejections are projected to be higher than the 2016 election — a major problem since mail-in voting is a necessity during the pandemic.

Election Protection, a nonpartisan coalition that promotes equal opportunity voting, has a hotline to call if you are turned away from your polling place. They’ve plugged their services on social media when voters took to Twitter to share stories of racial discrimation and questions of citizenship at polling places.

“This is not the America we came to,” my dad said to me when we checked our voter registration together. This is not the America he had grown up visiting on vacation in his childhood. This isn’t the America that invited a skilled architect and his family and promised opportunity, but this is my America now.

I don’t fault my parents for taking pride in their hard work to get our family to this country, but I do fault this system for making them and many others sacrifice so much just to vote.

I’m lucky and grateful that my parents filed our application when they did. This month, Trump announced changes that made obtaining H1-B visas more difficult and expensive to sponsor specialized workers.

Now, this is my country. My country with over 200,000 dead from COVID-19 and an oncoming third surge; my country with an ongoing struggle of racism and civil unrest. But because this is now my country, it is now my civic duty to vote. And if you have the means and the time, now is not the time to sit this one out. I stood in front of a judge, I renounced the Philippines, the place of my birth and the home of my family.

$13,860. That is the cost of my vote. And I will use it to vote Trump out because he does not represent the America I want to live in. What will you do with yours?

Margot Reid • Oct 28, 2020 at 5:44 pm

That’s my roommate! Could not be more proud of you – America is fortunate to have you as a citizen!