The Task of the Liberal Arts

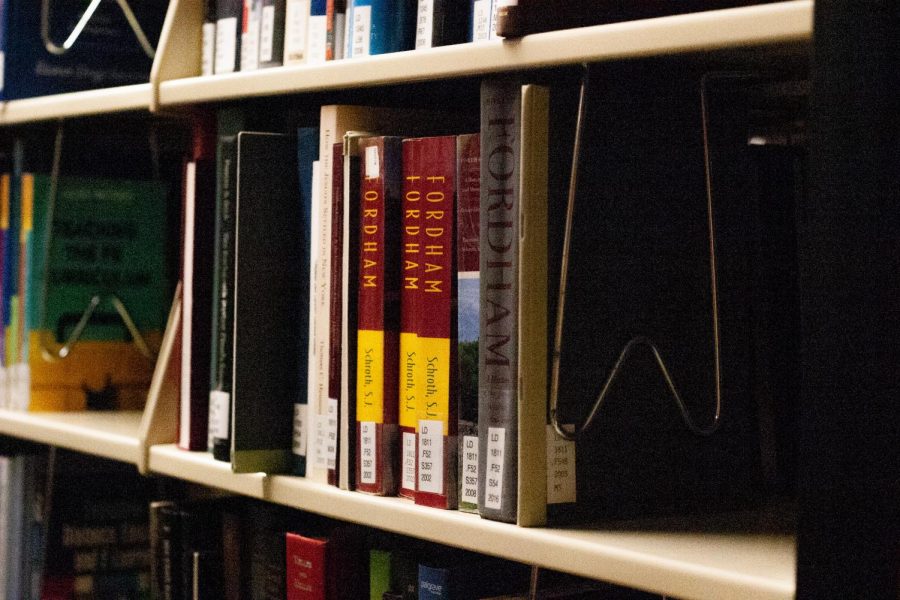

JOE ROVEGNO/THE OBSERVER

Fordham has many liberal arts students, but how many liberal arts human beings?

February 6, 2019

You speak of training students for a job. I speak of getting them drunk. You speak of learning. I speak of intoxication. The task of the liberal arts is to produce drunkards. Sobriety is the greatest threat to human existence, and the liberal arts are that holy means by which we corrupt students in the drunken madness of love.

But it is not liberal arts students we need so much as liberal arts human beings. University President Rev. Joseph M. McShane, S.J.’s 2017 address to Fordham’s incoming liberal arts graduate students noted that the “liberal arts” are really best thought of as “the liberating arts.” He thus returned the word to its primal potency.

It is not so much that I am here interested in the liberal arts as particular topics of study, as if they were mere pleasant hobbies. I have a higher allegiance to the liberated human self. And the proper vocation of this human self is love (eros). That alone is freedom.

Plato said that in love, the soul regrew its long-lost wings. Our souls’ present subjection to gravity is thus a kind of fallen state. I define gravity as the governing principles of this present world order: slavish economic structures, alienated, unfulfilling labor, spiritless consumerism, indifference to beauty, a general estrangement from the primordial wonder of being and the degrading demands of a mass society whose cultural aim is the production of mass-men, but never individual super-men (i.e. the infinite person fully realized).

We are more than capitalist units of economic productivity — the anthropology of the present order. Forgive my indecency, but can I now whisper the scandalous truth? Men and women have souls.

The task of a liberal arts education is to remind us of this. It is something one would never learn if wholly immersed in workaday society, for it implies a transcendence of that society. The liberal arts ought to be the place for transcendence. To achieve this, they must not be swallowed up by the demands of the marketplace or feel the need to justify themselves in relation to “utility,” “productivity” and other lowly, less-than-human words. They should bear prophetic witness to an alternate way of being.

Most defenses of the liberal arts are utterly unconvincing, because there is no real justification for studying the liberal arts except love, and love needs no justification — otherwise it is not love.

You are a great liberal arts student if you have learned to love greatly. I count this as the sole criterion for a successful education. And of course, this love is not limited to particular fields of study. The liberal arts are not ends in themselves. They are ultimately an invitation to a higher way of relating to the world, as is all art. This also means that a true believer in the liberal arts should not feel the petty need to claim the liberal arts as the exhaustive place where all beauty, love and transcendence are to be found (“there is no salvation outside the liberal arts”). Our dictum should instead be: “the glory of the liberal arts is the human being fully alive.” And therefore, we advocates of the liberal arts rejoice wherever we find such creatures, no matter their educational background.

This approach lastly demands that we feel no particular tie to colleges who merely have “liberal arts” in their title. The real question is whether these nominally “liberal arts” schools are actually fostering spiritual liberation. That is the single relevant concern. In light of our previous reflections, it would seem that models of the liberal arts centered on either a sterile “academic scholasticism” or the training of students into productive “usefulness” do not fulfill this liberating imperative.

And yet, it also appears these approaches overwhelmingly reign within the liberal arts today. Thus, when I consider the report in The New York Times that schools around the country are abandoning the liberal arts in order to stay financially afloat, my response is to shed a few tears (“if the salt has lost its saltiness … ”).

Perhaps this situation is good. Maybe the distorted perversion of the real thing needed to die. Perhaps this is a trend that should spread. True worship demands the destruction of false idols, as it were. Better to provide students with a more promising route to success in the workaday world. There is no shame in that. It is quite a service. But the liberal arts are meaningless unless they are animated by the love of higher things.

However, when the liberal arts are the training into love and wonder, they become an inestimable blessing, a shining city on a hill for a darkened world. This sort of liberal arts does not make us sober, “respectable” members of society. Spirited individuals cannot be tamed into a spiritless society. A student of the liberal arts presents an inherent challenge to the contemporary order, because a liberated being is always dangerous to a world that is less than free. And we have yet to be liberated until our lives are wholly intoxicated by love.