Beyond Intro Art History: Eastern Art at the Rubin

Downtown, Rubin Museum is as Much a Classroom as it is an Exhibition Space

June 6, 2011

Published: December 11, 2008

At the Rubin Museum of Art, there is no such thing as a passive viewer. Like it or not, you will be forced to learn something about the Buddhist and Himalayan art that fills this seven-story building which once housed a Barneys department store. Looking like the dream-turned-reality for a professor of art history or Buddhist studies, each floor contains works accompanied by written explanations and additional media sources. You’ll find paintings, sculptures, tapestries and photographs that are not used only for aesthetic purposes, but also to perform religious and traditional functions as well. The works are mostly historic, but certain pieces —such as an exhibition featuring photographs of life in Mongolia—are contemporary. Now, you might be wondering, “Well, why would I want to go?” The answer’s simple: if you’re even remotely interested in art, history, religion or other cultures, the Rubin is more than worth your time, and for the cheap admission price of $2 for college students, it’s a great alternative to those places on Museum Mile uptown.

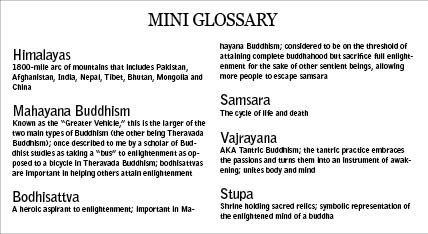

The visitor’s journey begins on the second floor, which features the museum’s permanent collection in an exhibition entitled “What is Himalayan Art?” Primarily portraiture and the personification of ideas, Himalayan works reflect the artistic, religious and cultural traditions of the 1800-mile arc of land that the Himalayan Mountains span. The floor is broken up into four sections pertaining to four questions: Where is it made?; Why is it made?; How is it made?; and What is going on? It feels like walking through an inverted textbook, where the striking illustrations have taken center-stage and the words are helpful but secondary to the images.

During one of my first visits to the Rubin, years ago, the guide tried to pull educated guesses from the group regarding the meaning embedded in some of the paintings, sculptures and tapestries. If you had no knowledge of the Judeo-Christian religions, he explained, and you went to a museum where there were recurring paintings and portraits of a woman and baby, how would you begin to comprehend the meaning? Well, first, he continued, by noticing patterns and repetitions, you’d realize that the subject being portrayed is important to that culture. It is the same with the art here. Many of the people visiting may be in the dark about Buddhism and Himalayan art, but you can start to deduce and hypothesize what is most significant after seeing similar representations throughout the museum.

At the Rubin, the visitor becomes both scholar and detective. With laminated cards explaining the meaning of works of art, hand gestures and body postures, in addition to magnifying glasses, audio headsets attached to short films, computers, books and photographs, you might not even notice how much information you’re absorbing. Now, don’t worry—though these attributes may sound too much like those inside a classroom, the museum is actually quite Zen-like (which makes sense, considering “Zen” is a school of Mahayana Buddhism). The tranquil museum looks like a work of art itself—solid, warm colors bathe the walls, soft lighting illuminates the artwork and an impressive, steel-and-marble circular staircase winds through the center, connecting all the floors.

At the Rubin, the visitor becomes both scholar and detective. With laminated cards explaining the meaning of works of art, hand gestures and body postures, in addition to magnifying glasses, audio headsets attached to short films, computers, books and photographs, you might not even notice how much information you’re absorbing. Now, don’t worry—though these attributes may sound too much like those inside a classroom, the museum is actually quite Zen-like (which makes sense, considering “Zen” is a school of Mahayana Buddhism). The tranquil museum looks like a work of art itself—solid, warm colors bathe the walls, soft lighting illuminates the artwork and an impressive, steel-and-marble circular staircase winds through the center, connecting all the floors.

A current must-see exhibition, whose only east coast showing is being held at the Rubin, is “The Dragon’s Gift: The Sacred Arts of the Bhutan.” Bhutan, a remote Himalayan kingdom east of Nepal and west of Myanmar, is the only Vajrayana Buddhist kingdom in the world and is interestingly one of the few countries in Asia to never have been colonized. Because the featured paintings, sculptures, tapestries and ritual objects are almost all still in active use at temples and monasteries, Buddhist monks can be seen daily at the museum blessing the objects and conducting morning and afternoon rituals which visitors can observe via the stupa, or shrine, that has been created in the museum space itself.

Few museums can compare to the approach taken by the Rubin. Everything, it seems, is focused upon education. While the Metropolitan Museum of Art is breathtaking, it is at times so overwhelming that you end up aimlessly wandering from piece to piece without absorbing anything. The Rubin—both because of its small size and because of the way it’s organized—is conducive to art education. When visiting the Rubin Museum of Art, this world where art and learning easily mesh becomes so engaging that you start to wish more museums would adopt this holistic method.