Ash Wednesday

April 18, 2012

Bernice Kilduff White & John J. White Creative Writing Prize Winner (Fiction)

On the morning of Ash Wednesday Maggie let the scalding water of the shower wash between her breasts in a river that divided around the delta of her pale belly, soft but stretched taut like a hard-boiled egg. The last few months had made her round and fleshy around the hips, and her swollen feet loomed up at her like red banana slugs through the humid steam. She leaned back against the icy ceramic tiles and delighted in the contrast between temperatures.

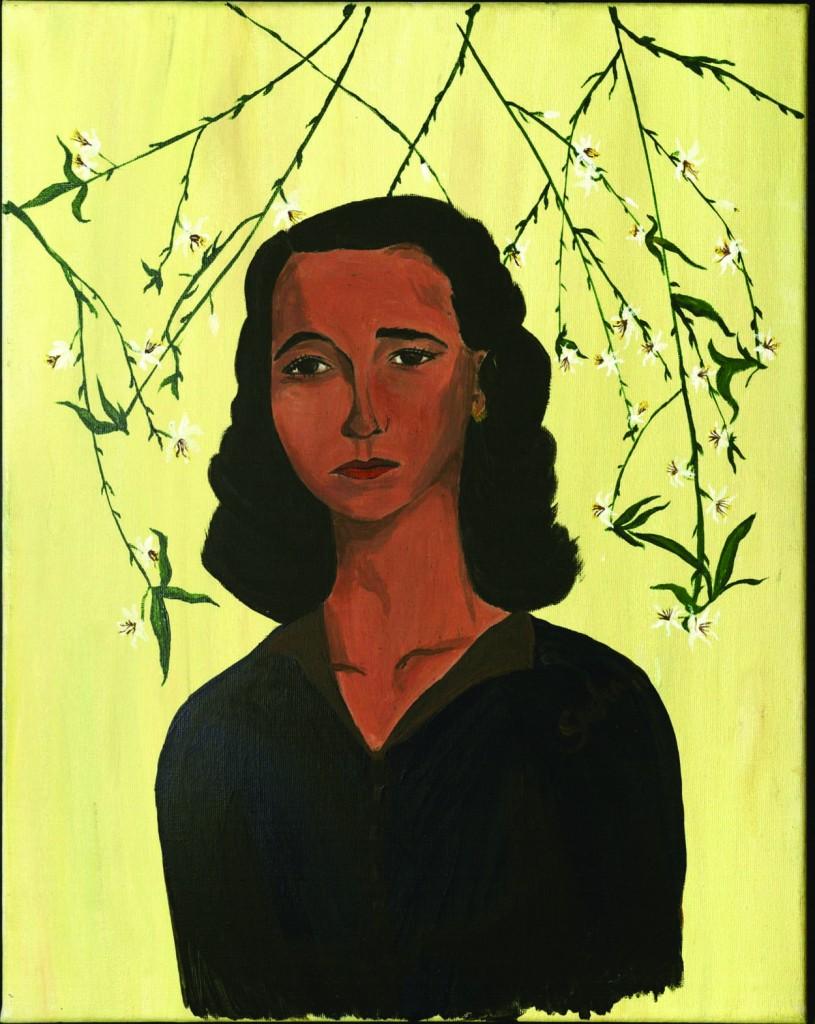

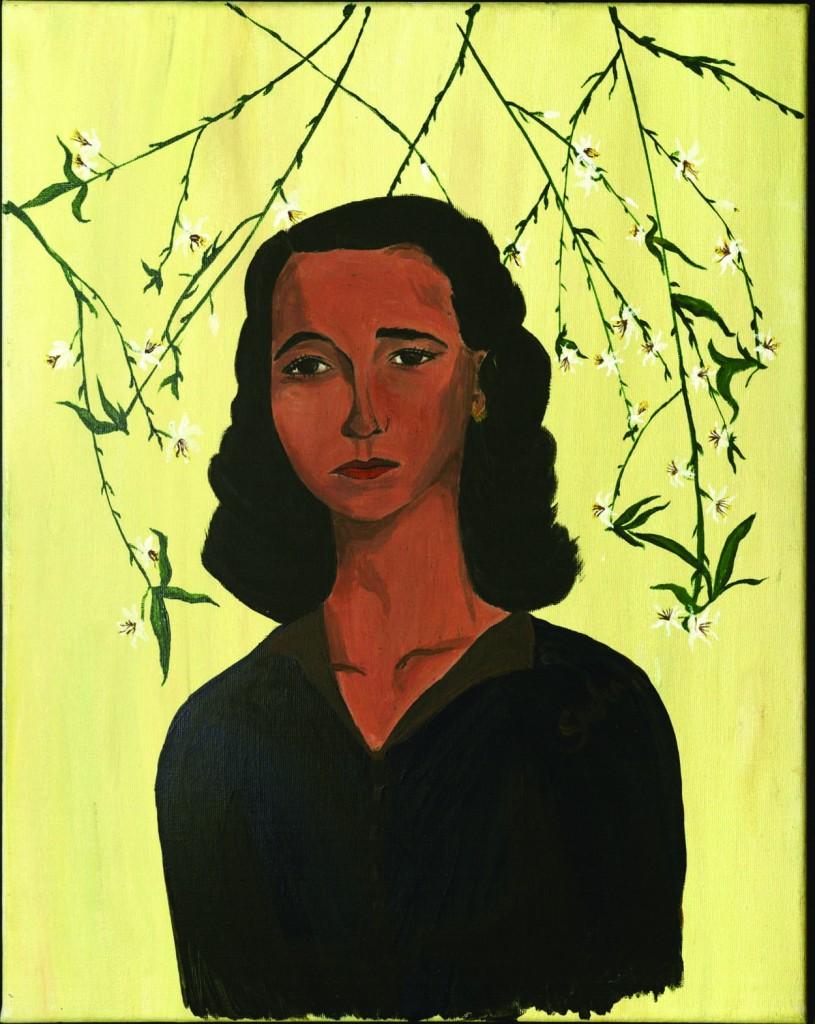

When she got out of the shower she vacantly dried her body with a towel, and after a while she stopped and let the towel fall over a puddle on the bathroom floor. She turned back and forth, and watching herself in the mirror rested her palms flat against her abdomen and tried to suck the new weight back in. The mirror fogged up and she squinted at herself as she applied black eyeliner and mascara to make her eyes look larger, and then carefully dabbed a ruby red stain over her lips and powdered her cheeks with rouge.

When she got out of the shower she vacantly dried her body with a towel, and after a while she stopped and let the towel fall over a puddle on the bathroom floor. She turned back and forth, and watching herself in the mirror rested her palms flat against her abdomen and tried to suck the new weight back in. The mirror fogged up and she squinted at herself as she applied black eyeliner and mascara to make her eyes look larger, and then carefully dabbed a ruby red stain over her lips and powdered her cheeks with rouge.

She went into the bedroom and after some deliberation put on a gray suit dress over a white turtleneck and nude pantyhose: bland, dull colors for a chronically dull-colored girl. She was running late; lunch was in an hour. Rummaging through the cardboard boxes Maggie pulled out and rejected several worn-down pairs of shoes before selecting a pair of low, sensible black heels that her mother would approve of. As she was closing the closet door she noticed the white post-coital shirt out of the corner of her eye, still dangling expectantly on a wire hanger pushed off to the side.

It was a beautifully sheer garment, oversized, refreshing and yet tantalizingly masculine, and she called it the post-coital shirt because it gave her the appearance of having just finished copulating. Maggie had been running a diligent but mostly fruitless campaign to increase her sex appeal since her years at Sarah Lawrence. Her mother would cry if she saw the post-coital shirt. Lucy was supposed to be the slut of the family.

After a moment of reticence she shut the door firmly on the post-coital shirt and left her apartment without eating breakfast.

Out on the street she bought a large black coffee from one of the carts and stopped to light a cigarette. Smoking was another habit picked up in college; it was fashionable among the young ladies, and eventually Maggie admitted to herself that she’d grown to like smoking for its own sake. The cigarettes were something all her own, apart from the family, apart from the house in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, with the saggy twin bed and worn out quilt that showed 1,504 quadrilateral glimpses of Poland.

She would have to quit, she thought as she finished the cigarette on the corner of McCarren Park, next to the flower stand that exploded with multi-colored blossoms even in the dead of winter. Happy hour with her coworkers was still a possibility, but she would have to abstain from alcohol and she didn’t like being around drunks when she was sober.

All around the flower stand sober sandy-haired women and men in mourning, bearing the solemn crosses of ashes and incense upon their foreheads, moved back and forth like pious ghosts going about their daily errands. All Polish people believe in ghosts; it’s an Eastern thing, a thing that comes from the cold, the dark and vodka-induced hallucinations. Maggie sucked into her lungs what little sunlight was present in the February afternoon and distanced herself from the Ash Wednesday specters.

She continued down the street. It was only a fifteen-minute walk to her family’s home, the place where she had grown up. Max would already be there—he was still at Brooklyn College and lived at home. It was unlikely that Lucy would show up at all. Her mother would have been cooking pierogi all morning. Sasha of course would be there. Her father would not be there.

Maggie crossed the street and lit another cigarette, fed the filter into her mouth; best to finish them now and then this would be her last pack. Her lips were full and large. The cigarette curled and dried up like a caterpillar, orange-red in the crisp light of the February morning. She inhaled nostalgically and watched herself turn back and forth in the front window of the flower stand, evaluating her stomach and the new chubbiness of her cheeks and chin once more. A Chinese man pushed a bouquet of bright yellow geraniums into her face and she bought them to appease the man, herself, and, with any luck, her mother. She looked at herself again. It was unfair that her first time should have produced such a result. Lucy was the slut of the family, but her arms and legs and stomach were still thin and beautiful as reeds. Her mother would cry.

You have to tell her, Max said.

Crowded around the lunch table with Max, her aunt Mary, her mother, and her baby sister Sasha, her mother congratulated her on the weight gain. You’re finally starting to look like a woman, instead of like one of those twiggy anorexic twelve-year-olds that are running around all over Manhattan. But you haven’t been to mass. No. Sasha spit up formula onto the front of her bib. Her mother would cry if she knew, about the cigarettes, about Maggie’s belly under hot, hot clear water, about O’Brien, about the post-coital shirt hanging up in the closet with the top buttons undone. Her mother was again smiling sidelong at the roundness of her daughter’s new shape, prompting Max to leave the table without clearing his dishes away.

The creature growing inside of her was the product of a love affair, if you could call it that: a brief and clamorous encounter with a stranger, Nick O’Brien, who was in real estate and enjoyed wheat beer and greyhounds. It was unfair that her first time should have produced such a result. Lucy was the slut of the family. Her mother would cry. You haven’t touched the soup; you should eat now, remembering you won’t be able to later because we are fasting.

Maggie tried very hard to relax her jaw and forearms. She was not a teenager anymore. She was twenty-five years old. What better time for a child? People did that these days. Why should she live in fear of her mother? There was no reason for it. This was not Poland. Are you sure you’re not hungry? Now her aunt Mary had begun serving tea. If she was going to tell the time was now, before the tea was gone and her mother began washing the dishes by hand. After that her mother would be tired and would take Sasha to lie down with her in the empty marriage bed. Now was the time to tell. You have to tell, Max said. You can’t ignore it any longer.

Several hours later it was dark and it had begun to snow a little bit. Any warmth afforded by the sun had been absorbed away like a sponge soaking up hot, dirty water from the edges of the kitchen sink. Maggie lit her last cigarette and listened to the rumbling of the subway coming up through the grates below her feet and she thought of the electrifying third rail, and falling in, and yellow geraniums in a blue vase, and O’Brien, and Polish ghosts, and one hundred other things, as she inhaled smoke like it was the last thing on earth that mattered. She leaned against a lamppost and felt the snow melting on the top of her head, the cold seeping through her thick hair until it finally brushed against her scalp. She looked up, searched through the frosty air for a spot of brightness, but the sickle-shaped moon was obscured by aubergine and slate-gray clouds of ash.